Julie : You, however, have a problem with women.

Mr. Gone : [scoff] How perceptive… did you figure that one out when I kidnapped you, or tied you up with leather straps? OF COURSE I’VE GOT A PROBLEM WITH WOMEN!

The Maxx (1995)

The Cell (IMDB) is a 2000 science fiction/thriller film with a strong artistic pedigree. The director is Tarsem Singh, best known for surreal music videos. The costumes are designed by Eiko Ishioka who also did the costumes for Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and Singh’s later film The Fall (2006). The music was by Howard Shore, composer for the films of David Cronenberg.

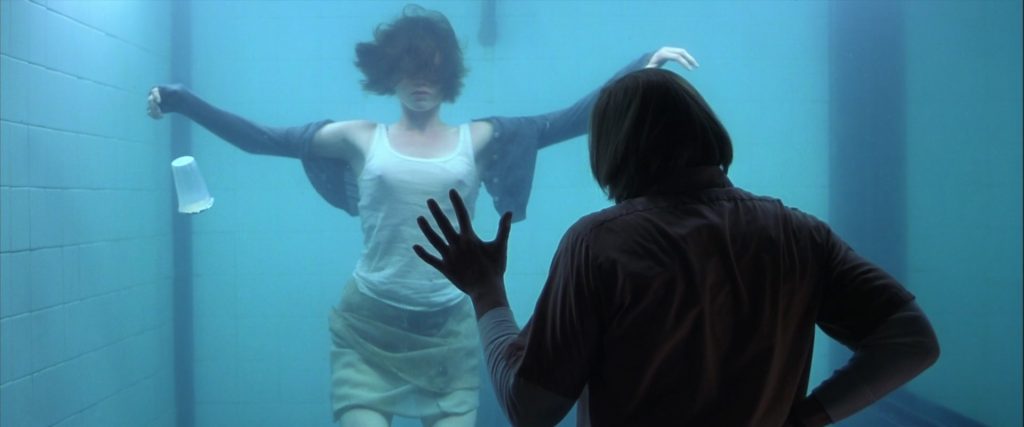

The story starts in familiar Gothic territory. A young woman has been kidnapped and imprisoned in a hidden glass box that is slowly filling with water. She’s the latest in a number of women murdered by Carl Stargher (Vincent D’Onofrio).

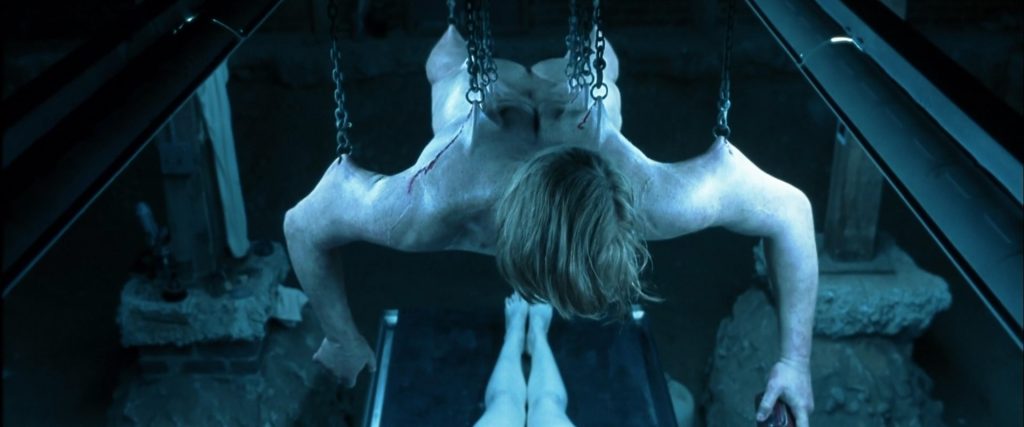

We see what Carl does with his victims post-mortem. First he bleaches the body white, then he uses an elaborate device to hang suspended above it by rings embedded in his back. While watching video of the victim screaming in terror, he masturbates.

Part of the process is dumping the body, wearing a custom-made red metal collar.

FBI Agent: “Some kind of a collar. Part of his methodology. […] He makes it for them. It makes him feel they belong to him.”

Just as the FBI agents led by Peter Novak (Vince Vaughn) close in on Carl, he succumbs to a chronic illness that puts him in a coma.

The long shot to find the woman before she dies is an experimental procedure for connecting minds. Catherine Deane (Jennifer Lopez), a child therapist, uses it to enter the minds of people in comas and communicate with them. Though reluctant to step into the disturbed mind of a serial killer like Carl, she takes the risk.

The design of the connection technology is beautiful and kinky. The people involved in the process wear suits designed to look like the red muscles beneath skin, with blue cloths draped over their faces. They hang suspended side by side, like in Coma (1978), from wires attached to the body-suit. Also, Catherine has what amounts to a safeword.

Tech guy: “We implanted a touch sensitive microchip in her hand, so if she wants to stop the session, or it gets too intense, she can give the signal and we abort.”

Inside Carl’s mind, the design really gets fantastic, collaged together from many different artistic inspirations.

In the first session, Catherine encounters a representation of Carl as a child, in a Damien Hirst-like exhibit that shows a horse sliced into sections that remains alive.

Child Carl leads her into the next space, a kind of gallery filled with representations of Carl’s victims. Their dead bodies are incorporated into wind-up tableaus of recognizable pornographic archetypes/fetishes: nurse, stripper, bondage doll, ponygirl, Amazon. It’s the heterosexual male erotic imagination at its most debased: dead clockwork dolls robotically repeating the same actions.

The Amazon (played by bodybuilder Kim Chizevsky-Nicholls) grabs Catherine and carries her to a throne room occupied by the monstrous “king” persona of Carl. He yells: “Where do you come from?” Catherine hits her escape button and screams.

After this, Catherine is reluctant to re-enter Carl’s mind, but after a heart to heart with Peter, she goes back in.

This time, she sees memories of physical, psychological and sexual abuse of young Carl, then finds adult Carl working on the body of his first victim. Julia tries to connect with him, and tells him that he shouldn’t have been hurt. She then tries to find out where the victim is being held but is captured by King Carl. Crouching over in a sex/rape-like position, he clamps a red collar on her neck, which draws blood.

A common trope in virtual reality fiction is being trapped in a false world. The technicians can’t pull Catherine out, and Peter decides the only thing to do is go in after her. Bring out the red suit.

Peter finds Catherine in an Orientalist fantasy, wearing a see-through dress, a red collar and a metal mask/veil, having succumbed to Carl’s fantasy.

King Carl captures Peter and tortures him by having his intestines pulled out slowly, while Peter keeps telling himself, “This isn’t real.” Finally, he brings up a traumatic memory Catherine shared with him, which snaps her out of it.

Peter and Catherine escape and Peter finds a clue that provides a lead on where Carl was keeping her. Peter leaves to find the damsel in distress.

Catherine, realizing that Carl will die soon, goes back under, but “reverses” the connection so that Carl will enter her mind.

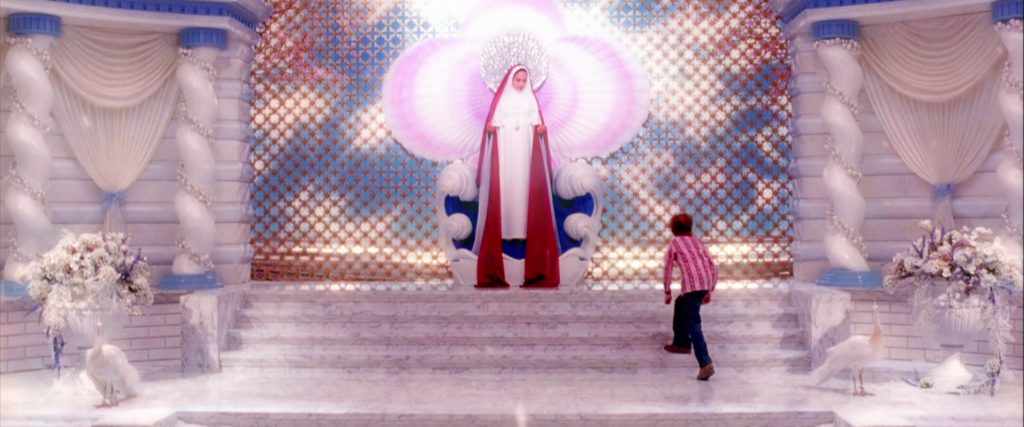

In her own dreamscape of a beautiful garden in red, white and blue, Catherine splits into her own archetypes, the healing and forgiving Virgin Mary-like figure, and the dark avenging huntress/dominatrix. She speaks with child Carl, but King Carl, in his most grotesque form, also enters. She pierces King Carl with crossbow bolts and a sword, and even rips out his nipple piercings, but realizes she is also hurting child Carl.

She’s the one with the empathy to see that within Carl, there’s both an abused, innocent child and a murderous monster, and that one can’t live without the other. She switches back into Virgin Mary mode, and gently lowers child Carl into the water to let him drown. In the real world, Carl finally dies.

This is intercut with Peter finding and freeing the victim.

As visually impressive as The Cell is, it also falls back on cliches of associating BDSM/fetish imagery with mental illness and evil. Carl can’t sexually or emotionally relate to real, living women and has to go through an elaborate and violent process to achieve any kind of masturbatory release at all. Even after death, they remain as pornographic cliches in his mind.

Though it isn’t emphasized, all of Carl’s victims appear to be blonde white women, linked to his practice of bleaching their bodies after death. Catherine, as a dark-haired Latina woman, breaks this pattern. She’s the one who breaks out of the odalisque-persona in which King Carl has imprisoned her, and adopts other archetypes for the final confrontation with Carl. You could interpret her as giving up the dominatrix archetype, which is just playing King Carl’s game, and returning to the mother goddess, choosing mercy over righteous anger. Or perhaps accepting that both have their purposes in her work.

I think you did a great job of bringing up the racial component of this film that I have not seen elsewhere. That’s a tricky subject, but I get what you are saying.