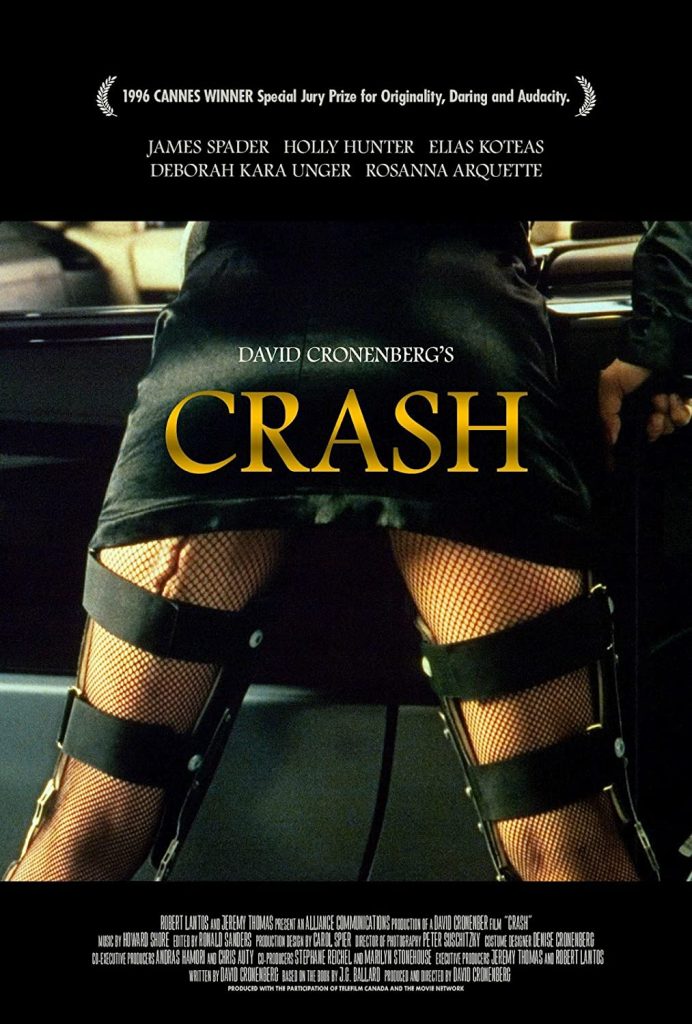

Crash (IMDB) is a 1996 psychological drama written and directed by David Cronenberg, based on the novel of the same name by J.G. Ballard.

Crash was a highly controversial film when it was released, and that is worthy of its own post. This post will focus on the film itself.

The film concerns James Ballard (James Spader), a film producer who, after a car crash, is drawn into a cult of car crash fetishists (for a lack of a better word) led by a visionary named Vaughan (Elias Koteas).

Crash shares (and predates) an aesthetic with two other late 90s “end of history” films: The Matrix (1999) and Fight Club (1999). They all take place in a generic urban landscape, almost completely without nature. The unformed protagonist is drawn from a false world of soulless Scandinavian design into a ragged underworld of imperfection and truth, guided by a charismatic visionary. Even the cars are similar. In Crash, Vaughan drives a battered 1962 Lincoln Continental convertible with suicide doors. In The Matrix, Morpheus drives a 1965 Lincoln Continental hardtop with suicide doors, though his is black and shiny.

“Fetishist” is only a provisional word to describe the experiences of James and the other characters. In the immediate aftermath of James’ accident, the woman in the other car, Dr. Helen Remington (Holly Hunter), exposes her breast to him in trying to escape, even though her husband has just died. James feels a connection to her.

Later in the hospital, James’ broken leg is encased in complex hardware, piercing his skin. In the hallway, he meets Helen, and a man named Vaughan, who carries a briefcase full of pictures of accident victims. Vaughan examines James’ injury, in a way that may or may not be seen as flirtatious.

The fascination with automobile accidents and the resulting injuries to both metal and flesh is the central premise of this film. Whether this is primarily sexual or incidentally sexual is debatable. It resembles certain documented real world kinks, such as:

- Salirophilia (arousal from soiling object of desire) and mysophilia (arousal from dirty objects)

- Pedal pumping, arousal from watching women pump the gas of stationary cars

- Acrotomophilia, attraction to amputees, and apotemnophilia, attraction to the idea of being an amputee (now called body integrity dysphoria)

- Stigmatophilia, arousal from attraction to scars

- Mechanophlia, attraction to machinery

- Symphorophilia, arousal from arranging and witnessing disasters

Helen and James form a sexual relationship, having sex in cars in public places. Catherine appreciates knowing about his encounters with Helen. Most of the sexual encounters in this film are in public or semi-public places. Even James and Catherine mainly interact, and have sex, on their apartment’s balcony.

Helen and James attend a kind of performance art piece, in which Vaughan, a stunt driver, and a race driver named Seagrave restage the car crash that killed James Dean in 1955. There’s a strong emphasis on authenticity in this performance, with real cars and no safety harnesses or padding. However, it definitely is a spectacle, as the middle-aged, balding and pudgy Seagrave, who drives Dean’s car, is dressed in the red jacket outfit Dean wore in Rebel Without a Cause, which presumably he wasn’t wearing during the fatal crash. Seagrave later talks about restaging the car crash that killed Jayne Mansfield, which would include him dressing in drag.

James and Helen hang out in Seagrave’s house with Vaughan and other hangers-on, watching videos of auto crash tests. This includes Gabrielle (Rosanna Arquette), apparently an accident victim who wears heavy braces around her legs and torso, suggestive of both armor and bondage gear. Gabrielle is an object of desire among Vaughan’s clique.

When the VCR glitches, Helen seems to jolt out of a trance. A moment later, she jerks to her feet and demands to keep watching it. Gabrielle says she has other tapes, Helen says she wants that specific tape. When the tape resumes, she calms down, and sits between James and Gabrielle, who start to fondle her sexually.

James, talking to Vaughan on one of their night drives in Vaughan’s battered convertible, says, “It’s all very satisfying. I’m not sure I understand why.”

He uses “Satisfying” instead of “hot” or “beautiful.” It’s the same word that is often attached to a certain genre of video on Youtube. Sometimes these are for videos for “stress relief, calm and sleep”, which show things like manual or industrial processes like decorating cakes or slicing up lumps of clay with string. Less innocuous videos that are labeled “satisfying” involve picking at scabs, cysts, blisters and other flaws in human skin. These videos can rack up tens of millions of views.

Something is driving those tens of millions of views, but what is it? Is it sexual, or something else? The possibly related phenomenon of ASMR raises similar questions. The person who coined the term ASMR, who is not a medical or academic researcher but a lay practitioner, said she wanted something that sounded scientific to move away from sexual connotations.

Even Vaughan himself isn’t entirely sure what they are doing, and has no interest in mainstreaming it. When they flee from the authorities after the Dean crash performance, James wonders:

James: “Why are the police taking this so seriously?”

Vaughan: “It’s not the police. It’s the Department of Transport. It’s a big joke. They have no idea who we really are.”

What Vaughan and his followers are doing is so different that it isn’t even a crime.

In response to James’ “satisfying” comment, Vaughan says:

Vaughan: “That’s the future, Ballard. And you’re already a part of it. You’re beginning to see that for the first time there’s a benevolent psychopathology that beckons towards us. For example the car crash is a fertilizing rather than a destructive event. A liberation of sexual energy, mediating the sexuality of those who have died with an intensity that’s impossible in any other form. Now, to experience that, to live that, that is… that’s my project.”

We’ve seen that “sadism” and “masochism” were terms born of 19th century sexology, imposed from above by medical/legal authorities, but embraced from the bottom up by practitioners. Vaughan’s “benevolent psychopathology” parallels the way BDSM practitioners try to explain the positive value of kink while hampered by the baggage of Victorian pathology. Other films directed by David Cronenberg have explored the idea of the physical or mental self being transformed by outside contagions, such as the aphrodisiac parasites that run amok in an apartment building in Shivers (1975), or the skin graft that turns a woman into a kind of vampire in Rabid (1977), or the living computer games that plug into people’s spines in eXistenZ (1999). There’s always an ambivalence to these bodily transformations, an interest in the new possibilities of pleasure and bodily experience.

Michel Foucault, the French philosopher and practicing kinkster, wrote about how what he saw in gay male leather clubs was a “laboratory” of new forms of bodily pleasure, a new definition of “sex” that was completely divorced from mammalian reproduction or male-female gender roles. Vaughan’s coterie could be seen as similar explorers of new bodily relationships, discarding old dialectics of “male/female”, “gay/straight”, “beautiful/ugly”.

This is why the mutilated Gabrielle is more intriguing than the blandly beautiful Catherine. She and James visit a showroom for luxury cars, and she teases the salesman by exposing her body in her heavy braces, including a vulva-like scar on the back of her thigh. The sexuality of disabled people, and the visibility of their bodies, is one of the most contentious subjects of our culture, and this scene plays with that taboo to make the salesman and the audience squirm.

She tries to get into the driver’s seat of a luxury convertible with creamy leather upholstery.

Gabrielle: (to salesman) “I’d like to see if I can fit into a car designed for a normal body. Could you help me into it, please?”

He awkwardly tries to get her into the driver’s seat, looking at Catherine’s modified body as if it is a completely alien thing he doesn’t know what to do with.

Gabrielle and James share a laugh when her braces rip the car’s upholstery.

Later, they have sex in Gabrielle’s modified car, parked in a garage. The unfamiliar controls and levers of her vehicle are as intriguing as her braced body. Struggling to get into position for coitus, James changes tactics and enters the vulva-scar on the back of her leg, which is pleasurable for both.

Vaughan’s body, itself a mass of scar tissue, gets further marked up when he gets a medical tattoo of a steering wheel over his chest. He gets James to get his own tattoo of his car’s hood ornament. This leads to a sex scene betwee Vaughan and James in Vaughan’s parked car, in which their fresh, still-healing tattoos are treated as new sex organs.

Post-coital, James walks into a neighboring junkyard where he sits in a junked car. Vaughan starts his own car and rams the car containing James, twice, freaking him out.

James and Catherine go driving in Catherine’s tiny convertible, and find Vaughan chasing them and trying to ram them. Vaughan has apparently lost it, and he screams and flips his car off an overpass, landing upside down on a bus and killing himself.

The other characters have a kind of mourning around Vaughan’s wrecked car. James fulfils Vaughan’s dream of driving a wrecked car by acquiring his car and fixing it just enough to drive. He takes off in pursuit of Catherine in her tiny sports car, a kind of consensual automotive rape play.

He hits her car a few times, and then she swerves onto the media and crashes. James stops, gets out and finds her sprawled next to her wrecked car, her stockings and garter belt exposed.

Catherine: “I think I’m all right.”

James: “Maybe the next one, darling.”

They have sex right there on the median, with her body battered, as if she’s craving to be transformed and initiated the way Vaughan, James, Helen and Gabrielle were.

While Crash isn’t about BDSM per se, it is a fascinating and provocative exploration of alternative forms of sexuality, aesthetics, and bodily practice. It’s a very unsentimental work, which doesn’t shy away from the self-destructive side of this world. Most of the other films and video I’ve looked at either completely pathologize BDSM, or go out of their way to sugar-coat it in hope of acceptance. Crash presents an insider’s perspective, and really doesn’t care what other people think. Either you get it or you don’t.

The only time I ever saw this movie, was at a non-play party hosted by a member of a kink group. The movie was playing in one room and folks were watching it and talking. A lot of them seemed intrigued or upset by the movie; no one seemed turned on by it. It did generate some discussion but that was almost two decades ago that I saw it.

I’m currently reading The Crash Controversy which is a British book about the varied reactions to the film, from both critics and regular filmgoers. A lot of people seem disturbed by it because they don’t know to receive it, as porn or an art film or whatever.