I found another page on the Stalag novels, a sub-genre of porn/pulp novels published in Israel in the 1960s, and featuring sex-and-violence adventure tales set in concentration camps.

The books told perverse tales of captured American or British pilots being abused by sadistic female SS officers outfitted with whips and boots. The plot usually ended with the male protagonists taking revenge, by raping and killing their tormentors.

What’s fascinating about the Stalag novels is their relationship to the real life violence and horror of WWII and the Holocaust.

The Stalags were practically the only pornography available in the Israeli society of the early 1960s, which was almost puritanical. They faded out almost as suddenly as they had appeared. Two years after the first edition was snatched up from kiosks around the central bus station in Tel Aviv, an Israeli court found the publishers guilty of disseminating pornography. The most famous Stalag, “I Was Colonel Schultz’s Private Bitch,” was deemed to have crossed all the lines of acceptability, prompting the police to try to hunt every copy down.

The Stalags went out of print and underground, circulating in specialty secondhand bookstores and among furtive groups of collectors.

In keeping with pornographic tradition, these books had Israeli writers, editors and readers, but maintained the pretense of being real-life, first-person memoirs translated from English. Porn/pulp could say, in a distorted and altered fashion, what could not yet be said in polite, official discourse.

This aligns with other cases of historical trauma producing pornographic or quasi-pornographic media (Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Hiram Powers’ The Greek Slave, et al.)

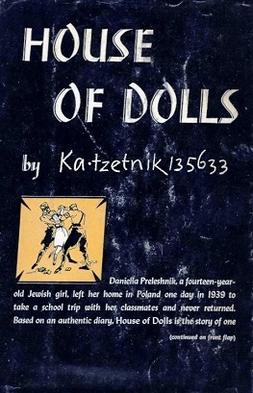

This ambiguity extends to Yehiel De-Nur, alias Ka-Tsetnik 135633 (“concentration camper” in Yiddish combined with his identification number), K. Tsetnik, Karl Zetinski, an author of

More provocatively, the movie contends that Stalag pornography was but a popular extension of the writings of K. Tzetnik, the first author to tell the story of Auschwitz in Hebrew and a hero of the mainstream Holocaust literary canon. K. Tzetnik “opened the door,” and “the Stalag writers learned a lot from him,” Mr. Narkis said.

[…]

One of K. Tzetnik’s biggest literary successes, “Doll’s House,” [or The House of Dolls] published in 1953, told the story of a character purporting to be the author’s sister, serving the SS as a sex slave in Block 24, the notorious Pleasure Block in Auschwitz.

Though a Holocaust classic, many scholars now describe it as pornographic and likely made up.

The book tells the story of a girl captured and forced into sexual slavery in German “joy divisions”. (This, incidentally, was the origin of the name of the British post-punk band Joy Division.)

The House of Dolls (full text in English) is the site of multiple, divergent discourses: some see it as historical fact (and even teach it in high schools), some as literary fiction, some as exploitative porn, some as pure propaganda. Did De-Nur actually tell the story of his younger sister? Did he even have a sister? Was there a diary? Was there a real girl, or did De-Nur construct a composite of multiple real people in similar experiences? Or did he just make the whole thing up out of his imagination, a distortion of his own experiences in the camps, altered to be more commercial by playing on the tried and true “virtue in distress” theme?

This connects to De-Nur’s motivations as a writer: was he being factual about a reality that could only be comprehended as pornographic/horror? Was he building an identity as an author that was an amalgam of multiple real sources? As De-Nur’s multiple aliases and pseudonyms suggest, we’re in a complex, ambiguous area where fact and fantasy blur, and fantasy may point to a greater truth than the merely factual, but also where fantasy may obscure the literal truth.

After all, many pro-slavery writers criticized Harriet Beecher Stowe and her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, calling her a “peddler of smut” and debating the factual accuracy of her book. Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind dismissed Stowe’s book as pernicious fabrication, for example.

De-Nur was scheduled to testify at the Eichman trial, but he fainted before his testimony properly began. It’s a frustrating detail, as if he is deliberately refusing to speak in terms of the literal truth, and preferring to speak in the poetic mode.

Even if De-Nur had no exploitative intent, his works like The House of Dolls and Piepel (about Nazi abuse of young boys) is said to be the inspiration of the later Stalag novels, a case of “vulgarization” (cf. novels of sentiment decaying into the Gothic novels).

Meanwhile in American, men’s adventure magazines of the 1940s through to the 1960s (known as “sweats” because they generally featured paintings of perspiring blue-collar men in peril on the covers) had their own Nazi-exploitation imagery.

Some were “virtue in distress” images, with women menaced by thugs in Nazi uniforms. Others showed men at the mercy of female SS officers, who had only the thinnest of historical justifications.

Of the 55,000 guards who served in Nazi concentration camps, about 3,700 were women.In 1942, the first female guards arrived at Auschwitz and Majdanek from Ravensbrück. The year after, the Nazis began conscripting women because of a guard shortage.

The German title for this position, Aufseherin (plural Aufseherinnen), means female overseer or attendant.

Female guards were generally low class to middle class and had no work experience; their professional background varied: one source mentions former matrons, hairdressers, street car ticket takers, opera singers, or retired teachers.

Volunteers were recruited by ads in German newspapers asking for women to show their love for the Reich and join the SS-Gefolge (“SS- Retinue” an SS support and service organisation for women). Additionally, some were conscripted based on data in their SS files. The League of German Girls acted as a vehicle of indoctrination for many of the women.

As discussed previously, the Nazi dominatrix is an attempt to link deviant sexuality with deviant politics, not to mention carrying unpleasant misogynist connotations (i.e. the belief that given the opportunity, women will be utterly depraved and cruel)