Cruz, Ariane. 2016. The Color of Kink: Black Women, BDSM, and Pornography (Sexual Cultures). New York: New York University Press

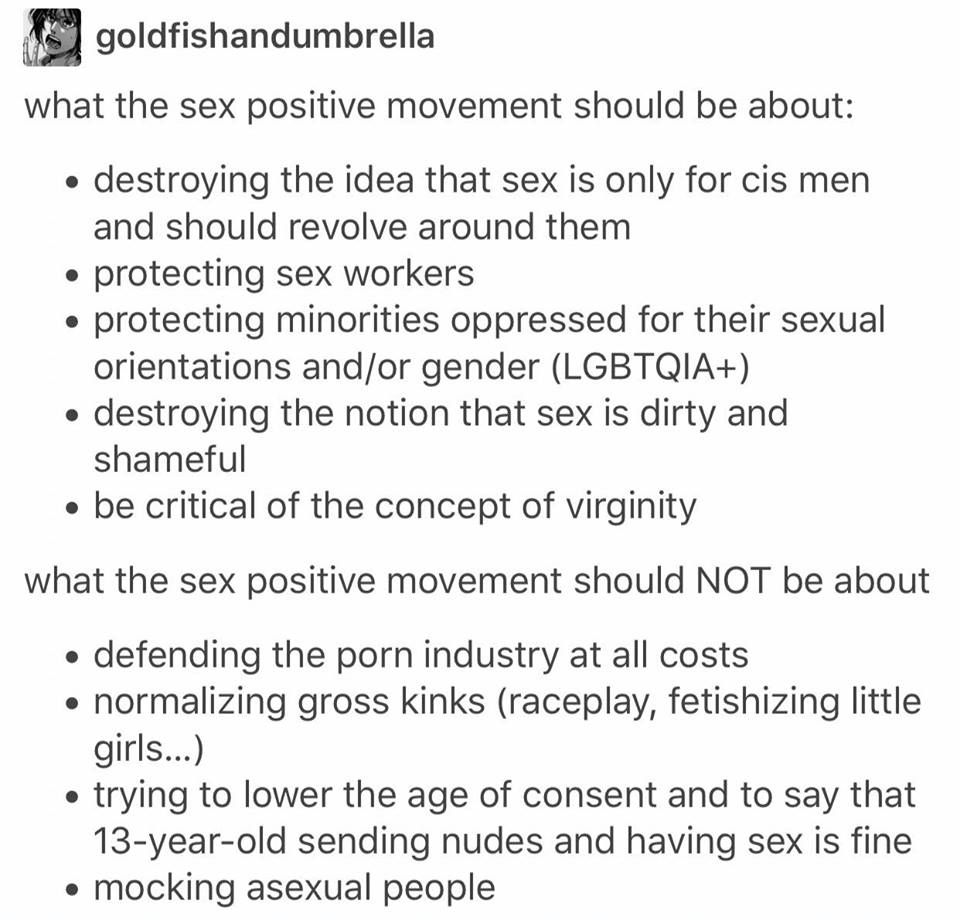

In the (now missing) tumblr post above, raceplay is called a “gross kink”, equated with “fetishizing little girls”, and placed outside the realm of sex positivity. Why exactly is raceplay on the other side of the line marked “edgeplay”? And where do black women fit within the current kink culture?

Still from Goodbye Uncle Tom, 1971

Ariane Cruz’ book deals with these questions directly, focusing on Black women in kink, and especially black women as submissives/bottoms. The cover itself shows a black woman’s face with a white rope gag in her mouth, daring the viewer to turn away. The image is taken from crystal am nelson’s video art piece Building Me a Home (2009), with bondage by Mistress Heart. nelson and Heart were part of the Bay Area Women of Color Photo Project, intended to increase the visibility and acceptance of women of colour in BDSM. [Pg.1]

In drawing on the symbolic yoking of black female BDSM sexuality to the memory of transatlantic slavery, the work invokes whiteness. If BDSM becomes a map for sketching out black female sexuality, whiteness stands as a signpost, a point of reference that often intrudes on the erotic scene to highlight its enactment of pleasure, power, and pain. In racialized BDSM performance and its dynamic representation in pornography, interraciality signals the political stakes for black women. [Pg. 4]

nelson’s work asks is how and from where we view the image of the bound black women, superimposing modern consensual BDSM and historical chattel slavery contexts.

…she [nelson] and her work ask: “What is that fine line between a representation of a contemporary space that is consensual and a representation of historical spaces or historical traumas that were non-consensual and is it possible to kind of make that leap from a historical reading to a more contemporary reading?”

This is a touchy subject, and one that many people have remained silent about.

What scholars have not adequately analyzed is how this mainstream popularity [of BDSM] perpetuates an understanding of BDSM that fails to consider how it is deeply informed by racialized sexual politics. Race is marginalized in both the scholarly literature and popular media about BDSM, contributing to the impressions that it is not something black people do, or should do, and/or that race is not a salient factor in the power dynamics so essential to the practice. [Pg.10]

It seems that many people, black and white, are invested in the idea that BDSM is something white people do, and refuse to even consider the possibility of masochism in black women.

…my work focuses on the unspeakable pleasures in and of black female abjection as a mode of racialization. Such pleasures coalesce in race play— a BDSM practice that explicitly plays with race– which, as I argue, is not a peripheral sexual practice relegated to the perverse margins of BDSM and pornography but is rather a powerful metaphor of black female sexuality that evinces its constitutive interplay of race, pleasure, trauma, and abjection. [Pg.21, emphasis in original]

Cruz does not condemn the racialized depictions of black women in kink or porn, and sees raceplay as a new possibility for black female sexuality.

While the antebellum legacy of sexual violence on black female subjectivity and on representations of the black female body is substantive, how black women deliberately use the shadows of slavery and engage antebellum sexual politics– aesthetically, rhetorically, and symbolically– in the delivery and/or receiving of sexual pleasure has not been adequately considered. I am interested in how the evidence of slime– a staining sludge of pain and violence– becomes a lubricant to stimulate sexual fantasies, heighten sexual desire, and provide access to sexual rapture. [Pg.32]

The debates over black women in kink bears a strong resemblance to the debate between radical lesbian-feminists and lesbian sadomasochists. Cruz cites as opposing examples Audre Lorde‘s essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power” and Tina Portillo’s “I Get Real: Celebrating my Sadomasochistic Soul” in Leatherfolk, and tries to find a middle ground between the two positions.

How do we acknowledge what matters— the historical, social, and political contexts that script slave/master and Indian/cowboy scenarios while accessing pleasure in their staging? [Pg.37, emphasis in original]

In her essay in Against Sadomasochism, Alice Walker condemned the image of a consensual black female slave in the 1980 documentary S/M: One Foot Out of the Closet, and wrote that “Regardless of the ‘slave’ on television, black women do not want to be slaves. They never wanted to be slaves.” Yet in the same essay, she uses the image as a teaching tool, instructing her students to “imagine herself a ‘slave’, a mistress or a master, and to come to terms, in imagination and feeling, with what it meant.”[Pg.38-39]

So how exactly does raceplay “work”?

Those who practice race play acknowledge that it is sensitive, demands a certain level of experience with BDSM, and is not recommended for dilettantes. […] setting race play apart from other “garden variety humiliation” on a kind of hierarchy of bodily practices reveals the currency that race brings into already proscribed BDSM performances. These experienced professional doms consider race play to be special. [Pg.52]

Cruz references the writings of Viola Johnson and Mollena Williams on the subject, and also references Margot Weiss’ Techniques of Pleasure, and her theory that the idea of “the scene” allows (white) practioners to disavow the influence of real world inequality and hierarchy. Cruz, however, says that “race play does not exhibit a disavowal of racial hierarchies or material institutionalizations of racial domination; it recognizes them.” [Pg.55]

What would happen if we understood the fantasy/reality divide as enabling not a disavowal of racial hierarchies and the power of racism but rather a rapture in them? I advocate reading race play as a way to funk and fuck with racism: a potential parody or mimetic reiteration that exposes the fabrication of race and challenges and reifies racial-sexual alterity and racism and a sexual relationship with these “racalisms”– a pleasure in their enactment, a getting off on, a fucking. Read this way, race play may be less of a neoliberal “fantasy of an escape from racism” and more of an escape in it or to it.[Pg.56, emphasis in original]

As a black dominatrix known as “the Black Fuhrer”, one of Cruz’ interviewees, points out, every kink is edgeplay for somebody. Putting raceplay in the “edgeplay” box is somewhat arbitrary, a gesture towards respectability politics.

I mean if we are going to try to make parallels between the world outside of fetish and inside of fetish and claiming that people who engage in racial type play are racist, then we are going to have to bring in domestic violence, assault and battery, verbal abuse, gay bashing, civil liberties. So we let some of this stuff go because no [sic] will bat an eye to a guy being caned, or nipple clamps, or labia clamps being put on someone, yet you know the use of certain words in racial context gets people up in arms. So you know, you have to be consistent, if race play is off limits then so is impact play, breath play, forced bi or any other sorts of things that aren’t kosher outside of fetish.[Pg.56-57]

However, Cruz cautions against lumping in race with other social hierarchies and obscuring their historical specificity.

Race uniquely augments this eroticization. Race play evinces how historically loaded black/interracial sex still is. […] black-white sex is always “more than just sex,” “always extraordinary,” black-white sexual intimacy in American society is necessarily informed by a national history of sexual racism.”[Pg.58]

While other forms of “identity play” in BDSM allow a person to say, afterwards, that they are not a pig or a dog or a slut, race is a social category that is harder to move in and out of. Rachel Dolezal may have passed herself off as a black woman for years, but Mollena Williams said, “I do race play whether or not I want to”.

Rachel Dolezal in a fashion show.

We might, then, think of race play as play with a certain type of fixity of race, not necessarily its fluidity. Race play complicates the theorization of BDSM play, challenging arguments that play rearranges power hierarchies. [Pg.67]

We also need to be careful about the moralistic discourse that BDSM must be healing and therapeutic to be acceptable. [Pg.67] However, Cruz says that raceplay BDSM has progressive potential for black women.

While BDSM might not heal a historical wound and/or allow for the enactment of some kind of redress– actual or symbolic– for black women, it might serve as a stage, or better yet a ring, for replaying primordial scenes of black-white sexual intimacy and the imbrications of pleasure, power, race, and sex.[Pg.72]

Cruz goes into the vexed histories of sadomasochism and race in visual media, and specifically pornography. Her key text is the fourth segment of Get My Belt (2013, produced by Kelly Madison), a high-production value hardcore anthology, which casts Skin Diamond as a black female slave in an unspecified, antebellum/Western scenario. (Diamond, incidentally, appeared in the softcore Submission TV series, in which she apparently functioned as a kind of tool for the white male lead to seduce white women into submission.) The last segment of Get My Belt, Cruz says, is merely the latest manifestation of chattel slavery’s hold on the erotic imagination, as seen in the 1970s sub-genre of plantation exploitation films (e.g. Mandingo, Passion Plantation) and in the 2010s films like Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave. [Pg.94]

Cruz also examines a less-lavish version of racialized BDSM in Danny Sisko’s custom-made raceplay videos. Sisko (a black man) has a harder time marketing his videos, as many sites won’t carry raceplay videos. [Pg. 103-105] He’s very aware of the historical context of black female submission.

I think I like to see the black woman on the bottom because I just think it intensifies the injustice and the cruelty of the, you know, the whole domination experience, you know. I just think there’s something to do with, like I said, the cruelness of it all that, you know with slavery and the history of racism in this country and the injustices that have gone on. I think that it just kind of intensifies the humiliation factor in the whole paradigm.[Pg.105]

He puts warning messages at the beginning of his videos, saying “This video was made for those who have a fantasy race play fetish; the actors are only role playing and the action is simulated”. [Pg.106] Raceplay remains something that has to be put in the special toy box, and often not even named as such.

Cruz describes an incident in 2004: TES issued a warning for its annual TES Fest Edge Play track. People complained about a workshop on race play, titled “Nigger Play; Free at Last!” led by a black male BDSM educator Mike Bond, the majority objecting to the word “nigger” in the title. In response, the organizer put up a warning for the edge play track as a whole, though without using the terms “nigger” or “race”. [Pg.107-108] Bond pointed out that his workshop is specifically about black submissions, which is not the same as black dominant/white submissive scenes. “submissive white men have always had the freedom to engage in their form of ‘affirmative action’ race play at the hands of ‘powerful black women.’ It’s considered cute and PC.” [Pg.108] (See this collection of letters on the incident.)

The TES nigger controversy sheds light on the racialized and gendered politics of BDSM, illuminating the vital ways race informs the practice to expose how the purportedly universal creed of BDSM consent is not so generic and comprehensive as one might think. For black BDSMers, consent is often not a kind of neoliberal individual agreement, but a larger contract that includes a responsibility to some phantasmic black community, allegiance to an invention of black authenticity, and homage to a particular recognition of history. [Pg.109, emphasis in original]

Cruz says that raceplay, a transgression within a subculture built on transgression, should be viewed as queer. “That is, the pleasure of race play is a queer pleasure, although often denied as such.” [Pg.116]

Indeed, our problem with pornography is akin to our trouble with BDSM: we register the eroticized domination and submission both as perverse, aberrant, harmful, and often non-consensual, while failing to interrogate the pleasure and agency potentially experienced in these power dynamics. Yet, a politics of perversion unveils the imbrication of pornography’s perverse pleasures– queer, BDSM, and interracial.[Pg.134]

The favorite insult of the alt-right is “cuck”, short for “cuckold”. That single syllable encapsulates both racial and gender anxieties around miscegenation. An entire genre of pornography is built specifically around exploiting that particular tangle of fear and desire. [Pg. 136] “Interracial porn” implicitly means black men with white women, and it draws on the deeply-rooted taboo of that particular combination to inform its scenarios. White men with black women, instead, is called “reverse interracial”. There is no transgression, or at least not at the level that pushes the emotional buttons that black man-white woman does. Black women are seen as always-already sexualized and accessible.

The term “miscegenation” itself was introduced in an 1864 pamphlet titled Miscegenation “was revealed to be a political hoax aimed at sabotaging Lincoln’s campaign for reelection, [which] played with important extant desires and phobias surrounding black sexuality, stereotypes of racialized sexuality, and sex across the color line that interracial pornography continues to engage.” It advocates for “negro” sexuality as an antidote for the decay of white American sexuality. [Pg.160]

This extends through the complex history of black women’s body in medicine (e.g. the mistreatment of the woman known as Saartjie Baartman, the invention of speculums by J. Marion Sims for probing the bodies of enslaved black women [Pg.201-202]) into the present day. On Kink.com, black women performers are tagged as “Ebony”, which “signals pornography’s continuing understanding of black female sexuality through skin color and the identificatory failure that black women experience and engender at the site of sexuality.” [Pg. 173] See also the complex racial fantasies, and emphasis on skin and skin colour, in the Munby-Cullwick relationship and in Memoirs of Dolly Morton.

As we’ve seen in before in researching this subject, Atlantic slavery has cast a long, long shadow in Western culture. Sexual fantasies are one of the myriad ways this cultural trauma has influenced the world.

However, the fantasy of racial-sexual alterity that pornography sells and BDSM traffics in is exceedingly ambivalent. It reifies these categories to stage their erotic transgression and performs a self-mocking hyperbole, a play, of race that underscores its own pleasure. As I have shown, pornography and BDSM eroticize not just the racial-sexual difference of the black female body but also the ambivalence of this difference– its instability– signaling a profound anxiety over the sameness of the black female body. Performances of black female sexuality in contemporary American pornography and BDSM are grounded in the shifting tectonics of desire and derision, sameness and difference. The colloquial phrase “it’s all pink on the inside,” which is simultaneously inclusive and discriminative and is rooted in difference and sameness, astutely encapsulates a number of contradictions at play within the spectacular repetition of black female sexuality.[Pg. 216]

Cruz is tentative about using the “cultural trauma” idea as a way of thinking about raceplay, and doesn’t want to define raceplay as a symptom of a pathology. She wants to “depathologize black women’s non-‘normative’ fantasies” and “foreground […] black female sexuality’s pleasures in the unpleasurable”.[Pg. 219] Raceplay, and its endless repetition so characteristic of sexual fantasies, might actually be a way of processing this trauma.

Raceplay, which the Tumblr post at the beginning of this post wanted to expel from sex-positivity, is transgression within transgression, queerness within queerness. As Alison M. Moore observed in Sexual Myths of Modernity, writing about the sexual fantasies engendered by another cultural trauma, “Fantasy (you don’t say!) is neither historically accurate nor rational.” It’s messy and disobedient, yet also a site of new possibilities.