Professor Marston and the Wonder Woman (2017). Director and writer Angela Robinson. IMDB

Who was Professor William Moulton Marston? A fantasist in the tradition of Frank Baum or Lewis Carrol? A guy who ruled a secret menage a trois with his wife and his younger student? A failed academic turned huckster and pornographer with a line in psychobabble? A loving father and husband with an unorthodox, closeted family?

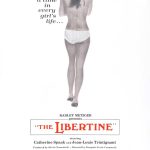

And what was his best known creation, Wonder woman? A feminist ideal? A patriotic icon? A “strong woman” who is constantly in chains? A punishing dominatrix? A lesbian in a man’s world? Kinky cheesecake? A role model for girls? A sex object for men?

Like a Rorschach test, an individual’s answer to those questions reveal more about the answerer than the subject. It’s easy to take a pessimistic and cynical view of Marston, his life, and his work. One post on Tumblr wrote: ”

To me it feels like episode 9362528494 of Women Can’t Have Anything when, in the wake of the Wonder Woman movie that empowered so many, we have the attention being put back on this origin story that’s essentially a drawn out bdsm sex game controlled by a man.

The framing device of the entire film is an inquiry into Marston, an interview between Marston (not long before his death from cancer in 1947) and Josette Frank, about the content of his Wonder Women stories. In those pre-Comics Code Authority days (before 1954), Marston’s Wonder Woman stories were hardly the worst offenders when it came to sexuality or violence in a medium supposedly for children. Perhaps what attracted the judgmental eye of others were the subtle hints of free-flowing, polymorphous perversity in the stories, the (barely) subtextual queerness. The inquiry extends into Marston’s academic career and personal life, with Marston answering questions like a man on trail for his life.

For Marston in this film, it’s always about emotional truth, which is contrasted with what might be called material or external truth. Marston’s inventions and interests are all about ways to reveal and express emotional truth: his DISC theory of emotions, his lie detector, his interest in bondage and roleplay (there’s no spanking or any other sadomasochism in their scenes together), and his fiction.

BDSM, in this film, is about emotional revelation, unveiling the sexual-emotional dynamics at work in supposedly everyday life. Marston’s guide into their new realm is the “G-string king” himself, fetish publisher and designer Charles Guyette (which probably never happened). On this side of the fantasy-reality divide, it’s the younger, beautiful Olive who becomes the dominant, the prototype for Wonder Woman, who wields the golden lasso that ties Bill and Elizabeth together.

And it works. Though Bill, Elizabeth and Olive are forced out of Radcliffe College, they form an unofficial three-way marriage, including children from both Elizabeth and Olive. The film goes out of its way to present Marston as a loving husband to both of the women and father to all of their children. He’s not the sultan of the harem, he’s a guy who happens to love two women, and furthermore he knows that the bond between Elizabeth and Olive is as strong or stronger than his bond with either of them. (In one respect, this is a love story between two women.) While this triad is necessarily in the closet, inside their little pocket reality, there is love and support. The bondage scenes between the three of them have the innocent pleasure of children at play.

It’s his wife Elizabeth who is concerned about external judgment, who sees her own life as a failure after her academic aspirations came to naught, and who sends Olive away after a nosy neighbor spies on one of their bondage sessions.

The film’s emotional climax is when, after Marston is diagnosed with terminal cancer, he invites back Olive to live with them. He gets Elizabeth to join him on their knees before Olive and plead with her to come back to them, and she agrees. It’s a kind of quasi-wedding ceremony, suggesting that Olive is the emotional foundation of their family, benevolently topping from the bottom. As the film makes clear, Elizabeth and Olive stayed together for decades after Bill’s death, and they named their children after each other.

This is not a documentary, let’s be clear. Apart from the scenes with Guyette, there’s also an improbable scene in which Olive lets Elizabeth and Bill spy on a sorority initiation, in which Olive paddles a pledge across her knees. I know that Marston wrote about this kind of thing, and strongly suspect he exaggerated or outright fabricated it. But the film asks us to accept an emotional truth that is different from a factual truth, to connect to the inner, emotional lives of the characters.

Does the film work a little too hard to make Bill Marston a good guy, completely without sexism or ego or selfish motives? Perhaps. Are there some ethically dubious things in this relationship? Yes. We’re at a time when it’s still rare for mainstream media to take an unprejudiced, much less positive, view of BDSM or polyamory. This makes Professor Marston and the Wonder Woman a rare, strange film that somehow works.

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

W.B. Yeats