Sleeping Beauty is a 2011 erotic drama film from Australia, directed and written by Julia Leigh. Amazon

Lucy (Emily Browning) drifts into paid sex work, as a lingerie-clad server at dinners for wealthy men, then takes a drug that leaves her unconscious as men touch her.

Leigh’s camera views Lucy, a young student, like an animal in a nature documentary. The first time we see her, she’s a paid subject in a medical experiment, swallowing some kind of device connected to a cable while a lab tech watches. She works a couple of low-stress jobs, as an office clerk and as a server, then hangs out in a bar. She lets herself get picked up by a couple of men, going through a game of coin tosses to decide who will have sex with her and when.

Money is a big issue in her life, which may explain the transactional way she treats most interactions. She struggles to meet rent with her room mates, and gets interrupted at work by her mother demanding money from her. The only person she seems close to is an alcoholic, suicidal man nicknamed “Birdmann”, whom she supplies with liquor and sex.

As she already views sex transactionally (along with most other human interaction), Lucy doesn’t hesitate to answer an advertisement in a school paper. She meet Clara, who proposes Lucy work as a lingerie-clad wine-server at private gourmet dinners for elderly, wealthy men.

Clara, the representative of the agency, assures Lucy that her vagina will not be penetrated in these engagements. Even if literally true, the statement doesn’t address all the other things, sexual and/or harmful, that could be done to Lucy. By focusing on that one point, Clara can maintain the fiction that what her agency does is legitimate, morally and legally.

Lucy agrees, studies how to do silver service and attends her first party. She wears white lingerie, to go with her petite body, fair hair, and young appearance. This contrasts with the other servers, brunettes in more revealing black lingerie, styled to look nearly identical.

These scenes are shot in a factual, deliberately un-sexy way. The male guests seem too libido-less and formal to actually do anything with the servers, treating them more like furniture than objects of desire. During the after-dinner drinks, some of the servers sit and cuddle with the men, but the implication is that the sexual part of the evening happens after Lucy is sent away.

Lucy accept her payment, but she burns at least one of the bills. Regardless, she does return to Clara’s agency and works at other parties. This brings in enough money for her to get a luxury apartment by herself, but she continues working her subsistence jobs.

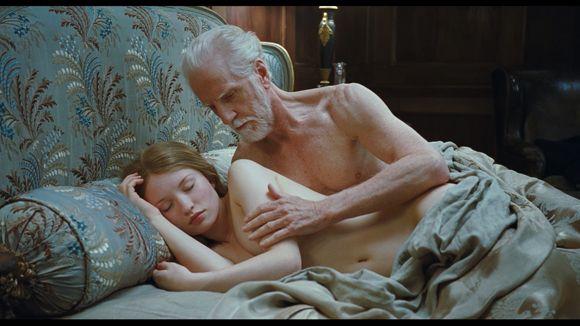

Later, Lucy moves to the next phase of Clara’s operation. Clara administer a drug that will put her to sleep for a few hours, supposedly without even dreaming, and men will have access to her body, though again Clara promises there will be no penetration.

The first man speaks to Clara about his feeling that the end of his life is close before he curls up with Lucy’s insensate body.

The second tells Clara he can’t get erect without viagra and anal stimulation, and verbally abuses Lucy, or tries to. As if frustrated by her complete lack of response to him, he lightly burns her behind her ear with a lit cigarette. Later, in the car ride home, Lucy touches herself behind her ear, as if she can feel it.

With the third man, Clara’s orientation has changed. The ban on prohibition is now only a request, not an actual rule. He attempts to lift Lucy’s limp, dead weight.

Meanwhile, Lucy’s studies are interrupted by a call from Birdmann, who has taken a lethal dose of pills. His last request is for her to take off her top and lie with him in bed as he dies. She tearfully complies. Later, we learn that his body wasn’t discovered until weeks after his death.

The French existential philosopher John Paul Sartre illustrated his theory about free will and bad faith with a parable about a young woman on a first date with a man.

… suppose he takes her hand. This act of her companion risks changing the situation by calling for an immediate decision. To leave the hand there is to consent in herself to flirt, to engage herself. To withdraw it is to break the troubled and unstable harmony which gives the hour its charm. The aim is to postpone the moment of decision as long as possible. We know what happens next; the young woman leaves her hand there, but she does not notice that she is leaving it. She does not notice because it happens by chance that she is at this moment all intellect. She draws her companion up to the most lofty regions of sentimental speculation; she speaks of Life, of her life, she shows herself in her essential aspect-a personality, a consciousness. And during this time the divorce of the body from the soul is accomplished; the hand rests inert between the warm hands of her companion-neither consenting nor resisting-a thing.

We shall say that this woman is in bad faith. But we see immediately that she uses various procedures in order to maintain herself in this bad faith. She has disarmed the actions of her companion by reducing them to being only what they are; that is, to existing in the mode of the in-itself. But she permits herself to enjoy his desire, to the extent that she will apprehend it as not being what it is, will recognize its transcendence.

Sartre, Being and Nothingness, 1943 link

In other words, the young woman avoids having to make a decision and accept the consequences, good and bad. Pretending you haven’t made a decision, or can’t make a decision, is, itself, a decision.

Even while she works for Clara’s mysterious agency, Clara keeps going to her office admin job, but does the absolute minimum. Eventually, she gets fired, which pleases her. Better in her mind to slack off until she’s fired than actually quit a job she neither wants nor needs. Being completely unconscious in bed with men somehow gets her off the hook for doing sex work. To be paid for being an object is ideal for Lucy

Other characters make their own complex denials. Clara tells one of her clients, just before he gets into bed with the unconscious Lucy, “You’re safe. There’s no shame here. No one can see you. But our rules must be respected. No penetration.” If no one is watching these sessions, how do they enforce the no penetration rule? The honor system? The cigarette ban from the second man proves that’s a sham. It’s a pretense, a game, a deflection.

If we apply Sartre’s ideas to Lucy’s behavior, we have to conclude that she actually is a submissive, an exhibitionist, and a masochist, and she engages in complex games to disavow her own desires. When picked up in the bar, she wants to be desired, but goes through the coin-toss ruse to avoid saying yes (and being called a slut) or saying no (and being called a tease).

For her fourth session, Lucy smuggles in a miniature camera and places it to record while she is unconscious. The client proves to be the first man again, who takes a lethal dose of Clara’s drug in order to die in bed with Lucy. Lucy reacts with sorrow and anger when she realizes she has been sleeping next to a dead man, much like Birdmann. She realizes that the other person has played the same game as her, and won.

Sleeping Beauty isn’t exactly about BDSM, but it does give some food for thought about treating relationships purely as transaction, and how masochistic or submissive desires may manifest in perverse ways.

[…] embrace her experiences, but instead seems detached, even confused. It’s different from Lucy in Sleeping Beauty (2011); Ai seems like a person who has lost her way, and looks to others for direction. She watches Saki […]