Hellbound: Hellraiser II was released only a year after the original, with a larger budget and mostly the same cast. Clive Barker wrote the story and served as executive producer. However, the sequel gets further away from what I thought of as the main themes of the franchise.

The main antagonist is Dr. Channard, a psychologist and brain surgeon who does some questionable work with his patients. Unlike the hedonistic Frank Cotton, Channard is more of the intellectual. “We have to see. We have to know,” he says, as he operates on the exposed brain of a conscious woman. Though he presents an uptight image, he operates a hellish private ward in the sub basement of his institute, and his study is crammed with occult materials. He already knows about Cenobites and the boxes, and owns several of them.

Channard, having studied Kirsty’s case, acquires the bloody mattress where Julia was killed. He allows a disturbed, self-injuring patient to cut himself to ribbons, which releases enough blood to partially resurrect Julia, just as Frank was.

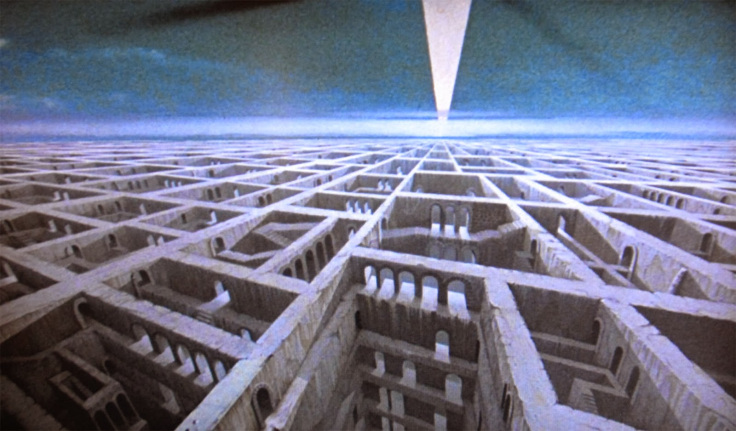

Skinless and leaving a trail of blood everywhere she goes, Julia seduces Channard, intellectually and sexually. They acquire more patients for her to consume, eventually returning her skin. Then they use Tiffany, a mute girl patient with a talent for puzzles, to open the box and create a portal into hell.

Note that the extradimensional realm seen in this film might not be “Hell” in the usual Christian definition. It might be something else entirely that human observers call hell. For simplicity, I’ll call it hell.

The rest of the action is Kirsty trying to free her father from hell, and Julia guiding Channard further into hell.

We get a glimpse of Frank’s private hell, where he is surrounded by sensual women who disappear the moment he touches them. For him, hell is being blue-balled.

Julia eventually pushes Channard into a machine that transforms him. Channard emerges from the machine, having gone full Cenobite, and says, “And to think, I hesitated.” This is one of the more interesting and unexplored aspects of the Cenobites, that they believe in what they do.

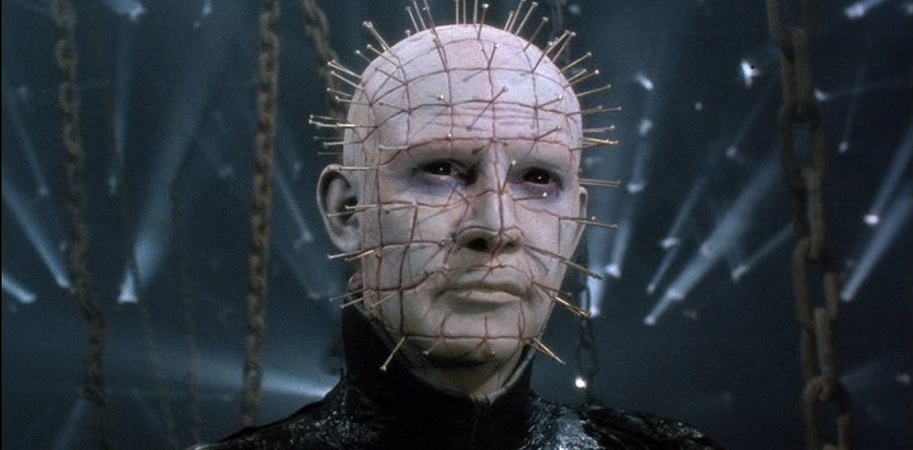

Cornered by the Cenobites, Kirsty shows Pinhead a picture of his former self, making him remember and hesitate.

Channard gets into a conflict over Kirsty and Tiffany with the other Cenobites, and kills them, making them revert to their human forms. He then chases the girls back into our reality, where Channard has been giving the boxes to his patients.

The girls go back into hell, and fight Julia for the transformed box. This results in Julia’s skin and clothing being stripped off, but Kirsty is also lost. Tiffany re-solves the puzzle box, transforming it back into a cube, and making the portals close. Kirsty disguises herself in Julia’s shed skin and rescues Tiffany from Channard, about to shove her into the transformation device.

Hellraiser II covers even more of the same territory as From Beyond. Both play with the idea that intellectual curiosity is a libidinal drive just like sex, and just as likely to go over moral limits. Go over the boundaries and you will be transformed into something other than human, and you’ll like it. This reflects common ideas that deviant sexuality is both seductive and repulsive, and crossing that line makes one totally depraved.

I would argue that what drives a person to find and open the puzzle boxes and then become a Cenobite is more interesting than what we get. There are hints of Frank’s life of hedonism in futile pursuit of satisfaction, and Pinhead’s past as a traumatized Great War-era soldier, who also acquired a puzzle box somewhere in the Middle East (again, the Orient). Channard is the most developed box-opener, a Faustian mad scientist.

Tiffany, with an autistic-savant talent for puzzles, opens a box, but the Cenobites ignore her. “It is not hands that call us. It is desire,” says Pinhead. That leaves Kirsty as the other box-opener. She must have the desires, but always evades the Cenobites.

Kirsty emerges as a trickster figure, making deals with and deceiving various powerful bad-father figures, such as Pinhead and Frank. She refuses to consummate their social contract and be confined to a patriarchal hell, always finding a way to slip out of the grasp of men. Pinhead basically calls her a tease: “Oh, Kirsty. So eager to play. So reluctant to admit it.” Whatever curiosity or desire is motivating her, it goes unexplored; a denial of female desire.

While there are some interesting moments, like the scenes of skinless Julia, Hellraiser II moves even further away from the themes of the original. Channard, set up as the series’ new chief antagonist, is just a gleefully sadistic megalomaniac, with none of the extra dimensions hinted at in Pinhead.