Cole, Shaun. ‘Don We Now Our Gay Apparel’: Gay Men’s Dress in the Twentieth Century. Berg, 2000 Amazon

If there’s a predominant theme in Cole’s book on the history of gay fashion in the twentieth century, it’s that gay fashion is always imperfectly mimetic, a tangled mix of “passing, minstrelization and capitulation”, to quote sociologist Martin P. Levine (pg. 3)

Even before the trial of Oscar Wilde, there was the trial and acquittal of Ernest Boulton (aka “Fanny”) and Frederick Payne (aka “Stella”) in 1871, two homosexual men who were also crossdressers and sex workers (Pg. 15-16). Ever since, those three categories have been conflated in the public mind (sometimes with justification). Gay men have overlapped with and been in fashion dialectic with other marginal groups (sex workers, soldiers, sailors, aristocrats, police, punks, bikers, artists, etc) for a variety of reasons: camouflage, recognition both covert and overt, political statements, defensive intimidation, generational differentiation, heightening male beauty, conspicuous consumption, personal fetishes or parody.

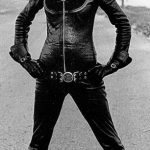

For our purposes, we’re looking at the archetypal leatherman look, the signifiers of normative masculinity exaggerated to the brink of absurdity, in stark contrast to the effeminate stereotypes of earlier decades.

While the associations of sadomaochism (S/M) were definitely there for some men, for others it was just an extension of the strict codification of gay dress. It projected an air of dark, brooding masculinity, with associations of the rebel, of Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1954), of the dominator. [Pg.107]

The biker look, which shaded into the leatherman look, was one part aspirational (gesturing towards Marlon Brando’s performance in The Wild One as an icon of masculinity, as well as Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising), one part protection (you looked tough to deter bashers), one part camouflage (if you didn’t own a bike, you could always claim it had broken down; some even carried a helmet), one part fetish (nothing quite like leather), and one part seduction (becoming what Quentin Crisp called “the great dark man” gay men dreamed of). The look straddled at least three groups: bikers, gay men into leather who didn’t do S/M, and gay men who did do S/M.

The development of the hankie code (following the display of keys) was an adjunct to this look. “…where previous [fashion] codes had signified sexuality, the new codes signified preference for particular sexual acts.” [Pg.112]

You can get an idea of how strong the image was, to the point that it could eclipse the identity of the person wearing it, comes from John Rechy’s 1963 novel City of Night. A sex worker is dressed up by one of his clients:

There’s a black leather jacket with stars like a general, eagled motorcycle cap, engineer boots with gleaming polished buckles. He left the closet door open, and I could see, hanging neatly, other similar clothes – different sizes.

It’s not enough to have the clothes to wear. He had the clothes already and then got other men to wear them.

The second movement in gay men’s fashion contribution to the emerging fetish style was punk in the mid-1970s, which was always about “bricolage” of assembling outfits from a variety of sources. Again, we get the theme of ambiguity, copying and impersonation: David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Alice Cooper. There is a rich cocktail of punks, transgenders, gays, hustlers and more, percolating around sites like Andy Warhol’s Factory. Deck Hebdige, author of Subculture: The Meaning of Style “identified two principal signifiers of punk: nihilism, or blankness, and, more importantly to this study, sexual deviance or kinkiness.” (Pg.148) The Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren duo picked up on the sexual appeal of the punk look and figured out how to sell it. “Malcolm found some under the counter catalogues with examples of weird fetish-wear items and we started to crossbreed the biker look with fetish wear.” (Pg.149)

At a certain point in the late 1970s, punk had to be de-queered to make it palatable for the mainstream. (Pg.147) Gays who didn’t care for the assimilation and upward mobility of the disco scene were left adrift.

Then you have sartorial overlap between the punk, fetish, goth and industrial subcultures. Even today, there’s still confusion over whether a given person dresses fetish because they like wearing the clothes themselves, because they like dressing up in public, because they do BDSM and wear the clothes as a kind of informal uniform, or some combination thereof. Of course there is a certain amount of appropriation by straights from gays in all this, just like many other forms of fashion, but really everybody is appropriating from everybody. I’m increasingly convinced that Hegel and his dialectics are the best guide through the kink world.

At the end of Cruising, the protagonist’s girlfriend experimentally puts on the mirrorshades and black Muir cap left over from his undercover assignment in the late 197os leather underground. The last shot is of the protagonist reluctant to turn around and face her, knowing that while this is a heterosexual pairing, something just a tiny bit queer has entered the equation.

Appendix: So where do women fit into this? Cole doesn’t have much to say. Subcultures tend to be resolutely masculinist and even ones that allow men feminine expression seldom support a corresponding masculine expression in women. The Muir cap or leather chaps will turn up in the attire of pro dominatrixes as a distant gesture towards the leatherman, though as masculine grace notes added to a feminine ensemble.

Appendix: Consider that in the Terminator franchise, the Terminator references the leatherman repeatedly. In the first film, he arrives in our present, naked, and has to steal clothes from a trio of street punks, grabbing a green fatigue jacket with leather collar and a chain around his left shoulder. Later, he wears a classic black leather biker jacket, sometimes over a bare chest, and a pair of clone-ish sunglasses. He’s a soldier/biker.

In the second, he wears black leather biker gear from the beginning to the end, having arrived at a biker shack in the wilderness. The promo images show him posing on a motorcycle, linking him to the outlaw biker/noble savage type who is redeemable.

The third film puts a comic twist on this. This version of the Terminator (who calls himself “an obsolete model”) arrives at a ladies night and takes his outfit from a male stripper. The masculine biker image he wears has become a cliched signifier that is mostly a joke for the amusement of women.

Also note that the antagonist in the second film, the T-1000, can take any form, but spends most of the film in the form of a uniformed police officer or a motorcycle cop. In the third, the antagonist is the TX, which also has shape changing abilities, and usually takes the form of a blond woman wearing a maroon leather outfit with heels.

There’s an interesting progression here in which the Terminator is initially associated with militaristic, outlaw masculinity, out to kill a woman, not for anything she’s done but for her reproductive potential. In the second and third films, the villain becomes the hero, allied with the woman and/or her child and pitted against villains who are at least somewhat gender-queer and are also defined by their ability to change their physical form. Recall Theleweit’s Male Fantasies, about femininity being associated with liquidity.