DelPlato, Joan. Multiple Wives, Multiple Pleasures: Representing the Harem, 1800-1875 Rosemount, 2002

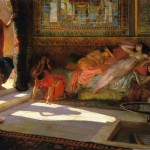

As shown in the painting above (John Frederick Lewis, Hhareem 1850), there’s a lot invested in the view of the harem as fantasy. The “truth” of life in a polygynous harem in the Arab world is almost irrelevant to the way the harem, and particularly the harem woman, figured in Western discourse. Feminists saw polygyny in the worst light, while apologists depicted it in utopian terms, a model of gender relationships in which men did not have to compete for women.

For a disgruntled middle-class husband the harem could be seen as an escape from the responsibilities of the nuclear family. It provided a tangible local for his fantasy of sex with multiple partners, women who were all compliant and undemanding. In this regard, the harem could function as the expression of wish-fulfillment. Because profligate sexual activity was considered one of the privileges of the aristocracy, the bourgeois male might use the fantasy of the harem as a vehicle for class envy. Conversely, the harem could become a projection of the fear of the femme fatale, who, in the company of her harem inmates, might overpower and devour the lone male. This is also implicit in the comment that the harem greatly contributed to the “impotence” of the Ottoman Empire.

Pg. 22

Philosophers including Montesquieu, Mary Wollstonecraft and Diderot used the harem to make political and philosophical points.

Artists like Lewis who depicted the harem or Arab women were in some weird netherworld between the erotic and the ethnographic. They produced highly detailed, “realist” paintings that were also eroticized, depicting harems, slave markets and the like. In some texts, there was a sharp contrast between the text of Emma Reeve, which condemned the harem and slavery, and the accompanying images by Thomas Allom, who showed Muslim women being coy and flirty (see Pg.75).

Perhaps crudely put, as European powers become the owners of collections of colonies, which they construct as the Other, their own process of identity-formation required that they split off the characteristics of both despicable master and weak/vulnerable outsider and project them onto, respectively, the male and female Other.

Pg. 29

This was a touchy political subject: British colonial officials saw the harem as slavery and exploitation, Turkish and Egyptian leaders saw it as home.

Pg.69 Could slaves be happy? How to explain the reports of happy, grinning slaves. And are black slaves happier than white slaves?

Pg.73 Unveiling and slave market scenes, fetishization of the veil.

[Re Lewis’s painting Hhareem, 1850] Abolitionists could project their sympathies for the indignation the slave suffers at the abridgement of her personal freedom. advocates for the toleration of the harem could see here a stunning record of picturesque ethnography. A middle-class viewer with no political interest could enjoy the exotic subject and its pictorial beauty. For all these viewers Lewis’s picture had a lascivious appeal as well. After all, Lewis has chosen to depict a narrative about a slave purchased primarily for her sexuality, and she is show partially unclothed.

Pg.86

For pro-Greek sentiment in Greek war of independence in the 1820s, white women menaced by dark men with slavery were a popular propaganda theme. (even though there were only about 600 Greek women in Egypt who hadn’t converted to Islam.)

See Delacroix’ painting Massacre at Chios, 1824, which painting depicts captives waiting for their fates in realistic, unglamorous forms, but one woman to the extreme right is depicted as nude, beautiful and highly eroticized, in mid-ravishment and bound to a Turk’s horse.

Even though harem women themselves were not technically polygamous, they took the brunt of Orientalist (or just plain bigoted) critiques of Islam’s supposed decadence. Harem women were thought to be ugly, bad mothers, lesbians, sluts in general, extravagant consumers, indolent narcissists, etc.