I don’t know if harem pants are still in in the spring of 2010, but a year ago Threadbared had an interesting post on the history and meaning of the harem pant, and by extension other pieces of “ethnic” attire.

In 1911, the same year that Morocco was named a protectorate of France, famed Parisian fashion designer Paul Poiret “introduced” the harem pant to avant-garde aesthetes alongside caftans, headdresses, turbans and tunics in an Orientalist collection. Those items deemed “traditional” and “backward” when worn on a native body were thus transformed as “fashion forward” when worn on a Western one, in what amounted to the blatantly uneven, and undeniably geopolitical, distribution of aesthetic value and modern personhood.

…

The harem, as an Orientalist fantasy of sexual excess and perversity (bearing no relation to actual practices of seclusion), depended upon imperial tropes of Muslim women’s sexuality as alternately available and licentious, or naive and repressed. In either instance, the Muslim woman was understood as a patriarchal property and an “undeveloped” personality. But as numerous feminist scholars note, Orientalist fantasies about the sexual proclivities –and possibilities– assigned to the “loose” clothing of the harem’s imagined denizens were often received as liberating for the corseted Western woman. For her, donning the harem pant (or the beaded veil or the fringed “Chinese” shawl) powerfully enacted a series of resonant fantasies about the ostensible transgression of bourgeois domestic life for a more spectacular and sensuous one, defined by shocking indulgence and theatrical intensity.

But in her essay “On Vision, Veiling, and Voyage,” about “cross-cultural dressing” by different groups of women (in this instance, European and Turkish women) at the turn of the century, Reina Lewis argues that the “thrill” of such cross-dressing for Western women was “predicated on an implicit reinvestment in the very boundaries they cross. Clothes operate as visible gatekeepers of those divisions and, even when worn against the grain, serve always to re-emphasize the existence of the dividing line.” About the European woman who indulges in sartorial tourism, “she can enjoy the pleasures of cultural transgression without having to give up the racial privilege that underpins her authority to represent her version of Oriental reality.”

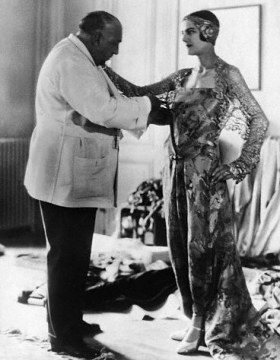

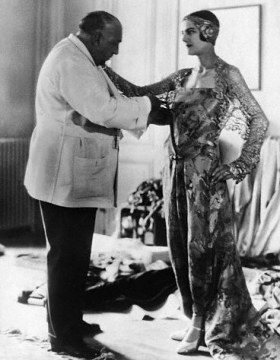

Paul Poiret and model, showing his "Oriental" influenced fashion

It also quotes a 2005 PopMatters post on Orientalism and Bohemianism in fashion:

In 1911, Paul Poiret, the famed French fashion designer, introduced a bold new line that marked one of the earliest and most famous appearances of “Oriental” fashion in the 20th century. Poiret’s cutting-edge “Oriental” designs included harem pants, caftans, tiered skirts, headdresses, turbans and tunics. In Raiding the Icebox, UCLA film professor Peter Wollen argues that Poiret’s designs embodied the rampant Orientalism dominating French culture at the time. Wollen describes the lavish “Thousand and Second Night” party Poiret threw to celebrate his new line. He says, “The whole party revolved around this pantomime of slavery and liberation set in a phantasmagoric fabled East.” According to Wollen, Parisian culture was in awe of the Orient, seduced by the Russian ballet’s performance of Shéhérazade and ecstatic over the publication of the new translation of The Thousand and One Nights; and Poiret’s fashions further whetted the public’s appetite for Orientalism. In addition, Poiret’s designs greatly impacted haute couture, and set the precedent for Orientalism in avant-garde fashion.

Lately, the term “harem pant” has come to mean any pant that is loose around the crotch, and in an ironic twist, the garment that was transgressively sexy in the early 20th century is now primarily seen as defiantly unsexy garment. It’s apparently popular with Muslim women who practice hijab.

Both article cited above speculate that it isn’t coincidental that the harem pant is back in fashion a century after its introduction, when the Western world is again engaged in wars in the Middle East and the status of Muslim women is much discussed. Perhaps the de-fetishization of the harem pants has to do with the deflation of the Orientalist fantasy of sexual adventure.

I don’t know if there was a specific fetish for harem pants, though likely as an aspect of a general Orientalist harem mise en scene in porn. I think there’s a difference between garments that are fetishized in and of themselves versus those that are part of a recognizable sexual trope or fantasy.

Perhaps some other garment is being appropriated for sexual fantasies in the developed world even as we speak.