Dr. Gloria Brame posted this video of vintage dominatrix photography, going back in the 19th century.

The Seduction of Venus blog has a more detailed discussion of Penthouse magazine’s first BDSM pictorial in the February 1976 issue. It includes some unpublished photos from the same shoot.

Taking a very different approach to the likes of Jeff Dunas’ and Earl Miller’s location-based, soft-focus romanticism he [photographer Stan Malinowski] posed his unnamed models in a studio with just a standard studio backdrop and bright, even harsh, lighting.

[…]

The text, as it is, consists of a number of four line verses of poetry (you can see some examples further down) which are very much themed on the idea of one woman inflicting pain on the other. No lovey-dovey “friends who became lovers mush” or, indeed, any suggestion that really the ladies, of course, prefer men, as most of the other girl/girl sets suggested. So the text is as radical for Penthouse, as the pictures.

While it may be a bit of a stretch to associate Penthouse with progressive views of female sexuality, this pictorial and its accompanying text at least breaks with the idea of female-female sex as an adjunct to heterosexuality or associated with pastoralism and coy “friends become lovers” narratives. Despite apparent reader approval, Penthouse did not take a turn to the hardcore after this.

This is obviously a much more professional piece of work than was probably common in BDSM porn of the time, and also in a publication that had a much wider distribution and larger readership than your typical under-the-counter bondage magazine. It may have been the first-encounter for a lot of people.

The Venus Observations blog focuses on the history of American newstand porn magazines, particularly the competition between Playboy, Penthouse and Hustler and their various spin-offs and competitors. In the mid 1970s, the major magazines were in a one-step-forward, one-step-back dance between the softcore, soft-focus, lots of pubic hair, arty aesthetic and the harder, sharp-focus, exposed labia aesthetic of later decades. Fear of alienating advertisers and censors kept editors nervous, but fear of losing market share made them experiment. E.g. a nude pictorial with a 22-year-old, very young looking model wearing a tank top with “12” on it.

In February 1976, Penthouse ran its first fetish-themed pictorial.

The real barrier breaking pictorial for February, however, was one called My Funny Valentine. Penthouse had had a (comparatively) few girl/girl pictorials before but this month they published their first fetish photographs. Dressed up in leather and vinyl the girls were depicted by photographer Stan Malinowski indulging in light bondage and whipping each other.

[…]

This pictorial, in the days when this sort of fetish was very underground and not displayed as a matter of course by female pop stars, caused some controversy in the press. Letters to the magazine, however, were universally appreciative (and Penthouse did, as we have seen, publish critical letters at this point) and asked for more.

At the time, mainstream magazines were nervous about showing a woman’s anus or labia in interior pictorials or their nipples on the cover, so this must have been a bold experiment for the publishers to show this kind of underground sexuality. Perhaps they discovered, as Irving Klaw and others had discovered in earlier decades, that fetish pictorials could tap a niche market without being sexually explicit.

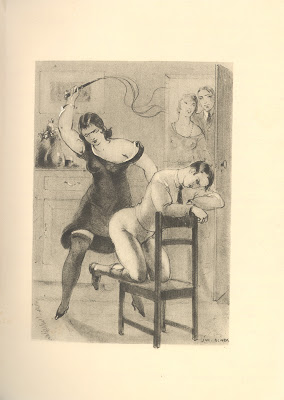

Another entry from A Carrefour Etrange is about Dresseuses d’hommes (Trainers of Men) by Florence Fulbert, published 1931, illustrated by “Jim Black” The emphasis here is femdom.

One of my favourite podcasts, the Masocast, has an interview with Domina Irene Boss. Boss has been involved in both the pro Domme scene and the BDSM video scene for a long time, and has good historical insights on both fields. She was in both at the ground floor, and was able to vacation in Hawaii from the proceeds of her DVD sales. These days, particularly after the advent of Clips 4 Sale, the video market is so diversified that this isn’t possible anymore.

She also has some inside knowledge of the Other World Kingdom in the Czech Republic, which is about as close to “the Club” or “the Marketplace” or “the Network” as we’re ever going to get in real life.

Punish Me. A film by Angelina Maccarone

Ranai’s blog has an interesting discussion of the German BDSM film Verfolgt (meaning “Hounded” in German), released as Punish Me in English. (IMDB) Briefly, a young male criminal and his older female probation officer begin a sadomasochistic relationship, with her on top. (I haven’t seen it so I can’t discuss the film itself in detail.)

There’s a lot of food for thought here, about the nature of male submission and female submission, its depiction in media (both mainstream and pornographic), and the influence of the commercial BDSM scene on the non-commercial. Fashion choices are only the most obvious form of this influence.

Elsa doesn’t need a costume. Inside subcultures, dictates of commercialisation and sexism still cause a good deal of female hetero beginners to ask ‘I want to dominate my man for the first time. What should I wear?’. This does not refer to people who actually have clothing fetishes themselves, but to people being collectively or individually pressured into costumes. It is immensely pleasant to see a female character simply going right ahead. Costume? What costume?

Jan and Elsa don’t buy and sell their interaction. They are in a personal relationship. Most people don’t get told by pervasive cultural narratives that the default of their sexuality is sex work. Heterosexual dominant women and submissive men get told just that. Our culture still overwhelmingly frames a man submitting to a woman as a commercial service which a man buys from a woman he is not otherwise in a relationship with. To the point of casting dominant and sadistic women as sex workers by default, and submissive and masochistic men as clients by default. To the point of pressuring many women into imitating prodoms and porn performers in their personal lives, and to the point of causing many men to act as if they were clients even in non-commercial, personal contexts (client mentality). To the point of, in the wider culture and in many sadomasochistic subcultures, effectively erasing and repelling women who happen to be sadistic and/or dominant in their personal lives. It is gloriously refreshing to see a story of a submissive man and a dominant woman doing their own sadomasochistic stuff inside a personal relationship.

A malesub-femdom love story would be so against the grain of culture’s rules about love, sexuality and gender that it might be illegible as a love story. People would look at it and scratch their heads, unable to understand it.

Just your daily dose of WTF

From the goofier end of the Silver Age comes this little oddity. The image reads a little like a dream, with the dreamer’s aggression directed at the image or effigy of the beloved, instead of the beloved itself, who watches heplessly.

Gatrell, Vic. City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London Walker & Company, 2006 Pg. 331-44

The fill title of the above print, published by William Holland’s shop in 1786 by James Gillray (at the time an up-and-comer in his field), is Lady Termagant Flaybum Going to Give her Step Son a Taste of her Desert after Dinner, A Scene Performed Every Day near Grosvenor Square, to the Annoyance of the Neighbourhood. For a print commissioned as a particularly nasty bit of character assassination and slander, it’s a very well-done work. The faces are uncaricatured and finely detailed.

As Gatrell puts it, “The print carried its own pornographic shadow.” William Holland shared shop space with a publisher of flagellation literature, George Peacock. Peacock published works like Sublime of Flagellation: or Letters from Lady Termagant Flaybum to Lady Harriet Tickletail, of Bumfiddle Hall (c.1777-85) and Exhibition of Female Flagellants in the Modest and Incontinent World (1777). The latter claimed that women engaged in the pleasures of flagellation of their own and others’ children, as much as men. (I.e. projecting fantasies of sadism onto women.) Flagellation themes frequently appeared in Gillray’s work.

The “Lady Termagant Flaybum” name was already known, at least among the wealthier men who could afford such prints, before it was attached to Mary Eleanor Bowes (1749-1800). Born to great wealth and raised to be an educated and freethinking (and somewhat irreligious) woman, Bowes (later Lady Strathmore) was the partial basis for Thackeray’s novel Bary Lyndon. Her main character flaw was rotten taste in men (or maybe the pickings were just slim.) In 1777, she fell for and married all-around scoundrel Andrew Robinson Stoney, “the libertine adventurer incarnate,” as Gatrell puts it.

Stoney managed to get control of Bowes’ estates and used it fund his profligacy, while verbally and physically abusing her. (This came out in the divorce trial a decade later.) He coerced her into writing her own Confessions, a quasi-pornographic work detailing her own flirtations and adulteries, her attempt to get an abortion and her irreligion. When Bowes finally had enough, separated from him and started legal proceedings, his abuse shaded into revenge, stalking her and attacking her character.

Gatrell describes commissioning the Lady Flaybum print as “a resort to image magic against his wife in a culture highly respectful of the image’s power.” Gillray may have been incoherently instructed, as Bowes allegedly had an “unnatural dislike” of her eldest son (not her step-son), and there’s no evidnce she had anything to do with flagellation other than Stoney’s claims. Other Gillray prints picked up on Bowes’ supposed preference to cats over her own children by depicting her nursing cats at her breasts while her son cries, not to mention drinking with and sleeping with servants.

A few months after the publication of the Flaybum print, Stoney actually kidnpapped Bowes with the help of armed thugs and a bribed constable, and fled into the wilds with her, pursued by constables and angry locals. (Life was imitating a Gothic novel.) At last, she was freed and Bowes was stopped in a country field. She went back to London.

The legal battles continued while Stoney was in prison, with Stoney using his wife’s extorted Confessions against her. They were openly published in 1793.

You could see this sordid affair as a collision between the old idea of libertinism and the idea of equal desire between the sexes, and the nascent cult of motherhood that would come to full fruition in the Victorian era. Bowes was as much of a female libertine as it was realistically possible to be, and Stoney’s principal attack on her character was that she was an abusive mother. She had no character to salvage, no way to turn public opinion to her side.

The two semi-pornographic works Stoney commissioned (so to speak) were used to control and to damage his wife via her public reputation (and sad to say, few people cared much about her situation.) What interests me is that these works may have been read as pornography by people who didn’t know or care about the real person they refer to. Furthermore, these images and texts may have hung around and been read by people long after Stoney and Bowes faded from public knowledge or been relevant. I can imagine people in later generations seeing the Flaybum print as inspiration for masochistic erotic fantasy. The two women in the print are depicted as beautiful, not grotesque caricatures as common in such prints.

Gillray was an interesting artist of this period. Whereas Rowlandson was erotic but light and fluffy and never without a humorous or satiric point, Gillray tended towards the blunt and the direct. The rule in high art was to show the moment before violence, but Gillray showed the event itself or its immediately and bloody aftermath. This is not to say that Gillray couldn’t be subtle and witty when he wanted, even about sexual matters.

As another example of fetishistic or perverse (mis)reading, this image could be also read as fodder for foot fetish fantasies.

The Hooded Utilitarian has a series of posts on the deep, deep psychosexual weirdness of the early Wonder Women comics, mainly from a post-Freudian perspective.

The writer argues that Marston’s ideal of “loving submission” is a parent-child relationship, distinct from the usual patriarchal “rule of law”. It isn’t enough to obey the law and keep your own thoughts; you must love your authority figure (shades of the ending of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.)

The impression I get from reading writer Marston’s stories is instability of roles and relationships. Wonder Woman shifts from dynamic omnipotence to helplessness and back in an instant. In one panel, she’s throwing around war profiteers like they were children, in the next, her mother Queen Hippolyta shows up and lifts her up like she’s a child. Harry Peter’s art accentuates this by playing fast and loose with perspective and scale. In the aforementioned scene, Diana is drawn as if she were child-sized relative to Hippolyta.

Ideas like this, of sexuality sublimated into fantasies of mind control, hypnosis, disguises, role-playing, transformation and the like, permeated much of popular culture, waiting to give people their first taste of kink.

Desmond, Marilyn. Ovid’s Art and the Wife of Bath: The Ethics of Erotic Violence Cornell University Press, 2006 Google Books

Desmond’s book starts off with telling how people objected to the inclusion of an informational panel on consensual sadomasochism at a feminist conference in New Paltz in 1997. This set off a media firestorm across the US. A similar controversy flared up in 1982 over the Barnard College conference that eventually led to Pleasure and Danger anthology, and was one of the inciting incidents in the 1980s iteration of the “sex wars.”

The New Paltz conference fifteen years later demonstrates that S/M remains an “alarming symbol,” even when its practitioners stress its contractual and consensual nature–as they did in the conference program–and even though popular culture, especially advertising and fashion (Versace, Gaultier) is saturated with S/M imagery.

Pg. 3

As such, violence against women constitutes a form of “structural violence” in the contemporary West. By contrast, the theatricality of S/M demonstrates that such hierarchies are inventions, and unstable inventions at that. Commercial and consensual S?M are aggressively policed in Britain and the United States while domestic violence has generally been tolerated in both countries as part of the status quo; perpetrators of domestic abuse, unlike S/M practitioners, are not classified as sexual outlaws.

Pg. 4

While S/M scripts parody the formations of power and fetishize the instruments of violence, such parodies and fetishistic operations frequently rely on historical configurations. Michel Foucault described S/M as a form of courtship, in which “sexual relations are elaborated and developed by and through mythical relations.”…. Premodern history offers intense opportunities for staing power in theatrical erotics since the semiotics of power relations in premodern cultures are popularly though to be crudely figured in terms of dominance and submission or starkly organized into social institutions such as feudalism or the Church…. Perhaps this is why Slavoj Zizek sees masochism and courtly love as direct reflections of one another….

Pg.4-5

Desmond cites an essay by Anna Freud, “Beating Fantasies and Daydreams” (1922), which follows up from her father’s “A Child is Being Beaten.” This shows an individual process of how one person takes a story and revises it repeatedly, turning it from a tale of violence to a tale of suffering and redemption.

Anna Freud’s case study suggests that narratives adapted–however loosely– from an identifiable past such as the medieval West provide a superstructure of fantasy that facilitates an erotic paradigm. If medieval scripts can be read through masochism–as Zizek sees it–or if they facilitate masochistic fantasy–in Anna Freud’s terms–perhaps the constructs of the medieval past might elucidate specific performances of contemporary heterosexualities, particularly in terms of erotic violence.

Pg. 5-6

What Desmond does in this book is trace out the genealogy of Western civilization’s views on the relationship between eros and violence.

Classical roman society was intensely hierarchical, and a Roman man was expected to keep order in his household (which included wives, family members and slaves) through words or blows. St. Augustine saw violence as an integral part of domestic order and affection, as an expression of marital love. Medieval marriage manuals, if not condoning violence against women, told women to suck it up and bear it. The consensus of laws in the period was that husbands had the right and duty to “correct” their wives physically, within some “reasonable” limit.

The root of this particular tree is Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, written around 2 CE. It’s a three-part elegy poem, with the first two parts telling the male reader how to seduce woman, and the third telling women who to act in such circumstances. Ovid wrote it in early days of imperial rule, when Augustus imposed new laws to strengthen marriage and penalize adultery, brought on by fear of declining birthrates and not enough citizens to maintain an army. (Cf. Foucault’s bio-power)

Marital reproduction thus became a legal obligation in order to further the goals of Roman conquests and colonial occupation. By contrast to such official policy, the Ars defines amor as an experience that can only take place outside of marriage, and it is completely silent on the reproductive consequences of heterosexual performance. The Ars thereby mocks the assumptions of Augustus’ marriage legislation that sexuality can be regulated by law.

…

The heterosexual script as it develops in the course of the Ars emerges from the structures of imperialism so that the praeceptor’s [instructor’s] discourse of sexual domination and conquest mimics the discourses of Roman coloniality.

Pg. 36

This is perhaps the most interesting aspect of Ovid’s work, that it was meant at least in part as a satire of the newly expansionist and martial state, which intruded into private matters. A Roman would have got the joke; a Frenchman a thousand years later wouldn’t. (This ties into two other themes I’ve noticed in the history of BDSM: imperialism/colonialism, and the misreading of texts.)

There is a masochistic side to this, when Ovid advises his pupil to occasionally and strategically debase himself before his domina (mistress, or woman in charge of household slaves). “Don’t think it a disgrace to suffer curses or blows from the girl, or plant kisses on her tender feet.” (2.533-34)

This voluntary subjugation–which the praeceptor offers as a theatrical role the lover might effectively adopt–is derived from the topos of the servitum amoris. In Latin amatory poetry, the metaphor of the lover as servus to an all-powerful domina provided a rhetorical formula for expressing the emotional agency of the puella [girl]– an agency which amounted to her ability to withhold affection and sexual favors from the lover; her ability to exercise any control over her own sexuality, that is, made her all-powerful… The praeceptor only suggests the pose of the servitum amoris as a means for the lover to consolidate his power over his puella.

Pg. 46

These ideas of how a passionate relationship should be conducted were carried into the centuries that followed. The great medieval lovers, Abelard and Heloise, referred to Ovid’s works, including the Ars amatoria.

The female reader of Ars amatoria 3 who disregards the irony of Ovid’s didactic discourse would find herself situated as the object of eroticized violence in an elaborate power play in which she could only acquire recognition through submission.

Pg. 57

Ovid’s semi-serious advice mixed up with Heloise’s uncle’s instruction to Abelard that “if I [Abelard] found her to be careless, I should constrain her severely.”

I’m not quite sure what to make of the Abelard/Heloise relationship. I know there was a reference to what sounded like spanking in Abelard’s account, but according to this book, this was not unusual. In the medieval pedagogical tradition, it was considered perfectly normal for teachers to beat their pupils, and otherwise be physically intimate with them. The scandal might actually be because of the fact that Heloise was remarkably well educated for a woman of her place and time, so this student/pupil relationship, usually confined to the homosocial/homoerotic all-male world, butted up against the heterosocial/heteroerotic world.

It didn’t end well. Heloise got pregnant, Abelard squirreled her off to a convent and her uncle castrated him. They continued to write each other. (This is the when the letters by Heloise start.) Curiously, she never mentions her pregnancy or child, perhaps echoing Ovid’s silence on the subject, so to speak.

The Abelard/Heloise relationship actually reminds me greatly the Munby/Cullwick relationship. Both relationships appear exploitative and intensely hierarchical at first glance, but on further examination reveal a much more complex interplay of fantasies, roles and power.

Heloise wrote to Abelard that she would rather be his meretrix (a high-level courtesan) than imperatix (the empress). (Pg.64) This is echoed in Cullwick’s statements that she would rather be Munby’s maid of all work than his bourgeois wife. In one of Heloise’s letters, she said that their relationship was not just teacher/pupil, but also father/daughter, husband/wife, brother/sister, all of which were based on the classical dominus/ancilla (master/slave) relationship. (pg. 62) (This is different from the more complex roleplaying of Munby and Cullwick, in which she was often the dominant role, both as a maternal figure and as a more masculine figure than Munby.) Heloise’s letters seem like she’s trying to top him from the bottom, demanding her recognition as his submissive lover. In effect, she’s saying he owes her attention and recognition, and that he isn’t playing his role properly.

So, were Abelard and Heloise a BDSM couple as we would recognize it today? Sort of. I think the difference is, and this is something that Desmond never quite puts her finger on, is that the word punishment in BDSM should always have quotes around it. In the ancient and medieval traditions Desmond writes about, violence is used as a punishment, not a “punishment,” as a means of controlling the subordinate party. If the subordinate party wants to be beaten, then the entire strategy falls apart.

Desmond’s book does raise the idea that violence and eros in Western civilization has been coupled together at a very deep level. She cites Foucault to say that Ovid’s poetry provided a kind of script that informed other depictions of heterosexual relationships in later times, a set of theatrical gestures that could be manipulated, re-read and mis-read.

Desmond also discusses the “Mounted Aristotle”, a visual and literary reference that began in the 13th century and recurs in many different works. The most common form is a older man, whose age and dress indicates his learnedness, on all fours, with a woman riding him as a horse, often wielding a whip. The story behind it, which has no basis in classical records, is that Aristotle was tutor to Alexander the Great in India. Aristotle chides Alexander for being too smitten by his wife or mistress, usually named Phyllis. As revenge, Phyllis seduces Aristotle, and he agrees to let her ride him as a horse. She also arranges for Alexander to watch this. (Note the elements of voyeurism and humiliation, common in fantasies.)

I bring this up because I want to make it clear that people should not look at this particular image and anecdote and immediately say, “Aha, people in the 13th century were kinky just like us.” The mounted Aristotle was viewed in a variety of different ways and contexts, including references to contemporary politics. It was not only an erotic image. It was also a warning against the seductiveness of women, yet also a rueful admission that even the wisest of men are susceptible. Yet the perverse erotic meaning is within the image, there to be read, and provide a seed for fantasy. In a horse-based culture, equestrian metaphors would have had a lot of currency.

The fantasy of the “mounted Aristotle” shaped the language of erotic violence in medieval French and English narratives so that a cultural notion of the scandal of female dominance could be cited visually or textually in equestrian images or metaphors. The erotic potential of such equestrian fantasies remains a recognizable feature of modern power erotics.

Pg. 27