Jay A. Gertzman’s article “1950s Sleaze and the Larger Literary Scene: The Case of Times Square Porn King Eddie Mishkin”, in eI15 fanzine, provides an intriguing glimpse into the proto-BDSM scene of 1950s America, particularly the previously mentioned publishing empire of Eddie Mishkin.

Mishkin employed fetish artists like Eric Stanton and Gene Bilbrew, as well as writers, some of whom wrote pornography under pseudonyms or house names to pay the bills while working on above-ground books or television.

One [of Mishkin’s writers], who wrote under the name “Justin Kent,” was held as a material witness for over a month. Both he and a woman unfortunately named Leotha Hackshaw stated that Mishkin told them to write about “rough sex,” with “strong lesbian scenes,” “high heels,” “perfume fetishes,” “bondage,” etc. He lent Hackshaw texts on sexual deviations, including Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis,so that her stories focused on spanking, whipping, and the “weals” left in male and female flesh by violent foreplay. Many of the booklets were illustrated by the fetish artists Gene Bilbrew and Eric Stanton. In appearance, these publications suggested cheapness and unreliability, an impression reinforced by a five-dollar cover price for badly edited, cheaply produced, typewritten texts some of which were nicely illustrated, but with line drawings unrelated to the narrative itself. Sample titles were “Screaming Flesh,” “Return Visit to Fetterland,” “The Hollywood Spankers,” and “Sex Switch.” Newspaper reporters, prosecuting attorneys, and judges noted that the appearance as well as contents of Mishkin’s booklets epitomized “dirt for dirt’s sake,” with no purpose other than to appeal to prurience to make as much money with as little expense as possible.

It’s interesting is that Mishkin had his writers working directly from a five- or six-decade old work of sexology, and other academic or semi-academic texts, to write pornography. For Mishkin, Psychopathia Sexualis was market research, a list of readership requirements to fill. Compare that to how many fetishists searched through Krafft-Ebing’s book (and it’s many pirate editions) for validation of their own desires. That book cast a long shadow.

Mishkin put huge markups on the books he published, but he at least paid his contributors well.

He paid between $100 and $350 per story, according to testimony at the 1960 trial. For a single drawing, Gene Bilbrew, who did illustrations for covers, got $30 or $35, and Eric Stanton, for interior work, got $10 or $15. According to the Department of Labor’s Consumer Price Index, $100 in 1959 would be the equivalent of almost $640 in today’s currency. All these deals were strictly in cash, which changed hands in one of Mishkin’s stores or in a bar called Dino’s on 42nd Street.

Mishkin’s contributors were also part of the NYC Bohemian subculture of the time, where you’d have CIA agents armed with LSD rubbing elbows with wife-swappers, writers, artists, models, prostitutes, homosexuals, lesbians, fetishists and the like.

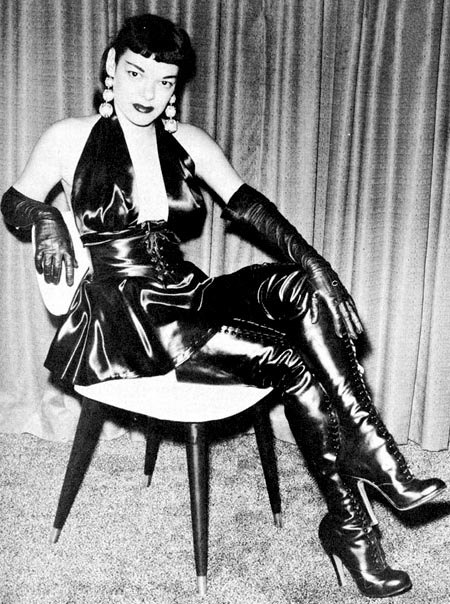

At the same time a surreptitious Midtown fetish and S-M scene was active. A publisher and distributor named Lenny Burtman was at the center of it. He and his wife, model Tana Louise, hosted swinging parties in their apartment. Burtman and several associates financed the film Satan in High Heels [1962], many scenes of which were shot there.

Mrs. Burtman appeared in his digest-sized magazines such as Exotique, “a new publication of the bizarre and unusual.” Many copies were seized in police raids on Burtman’s warehouse in 1958. Exotique, and other Burtman publications, were classified as deviant because of the leather, high heels, and attendant fetishes, to which the publisher appealed with stories, advertisements, drawings, photos, and correspondence from enthusiasts. Times Square bookstores carried his fetish booklets and magazines extensively, and his distribution system was more far-reaching than those of Mishkin or of Irving Klaw (whose booklets featuring bondage and flagellation were as notorious as Mishkin’s). It is probable that both Bilbrew and Stanton attended Burtman’s parties, if only because both illustrated Burtman’s publications.

Gertzman, following the research of Robert Bienvenu, says that Burtman wasn’t merely in the queer/kink scene to make money, but viewed himself as part of it, contributing to a community.

Unlike them, he was not only supplying furtive men with images which excited them for reasons they did not care to explore, but also filling the needs of people actively pursuing radical, deeply tabooed sexual alternatives. Burtman was a businessman not a creative artist, but he provided materials and a setting for an innovative and liberating style of expressing tabooed libidinous needs.

http://efanzines.com/EK/eI15/#sleaze