“Cool is conservative fear dressed in black.” Bruce Mau

On the last day of the Leather Leadership Conference 2010, I wore a red corduroy collared shirt in preparation for the flight home. It very quickly became apparent that how much I stood out in a sea of men and women in black t-shirts.

Sometime around 1820, black clothing for men came as a fad, but it never went. After the flash of men’s attire in the 18th century, the black or dark suit became the standard wear for all men in Europe, and even more so in the United States; Charles Dickens was considered something of a fop for his colorful attire when he crossed the Atlantic. There are several reasons for this: the new cult of masculinity as sober and rational, the Victorian cult of mourning, the rise of the Calvinist-capitalist bourgeoisie.

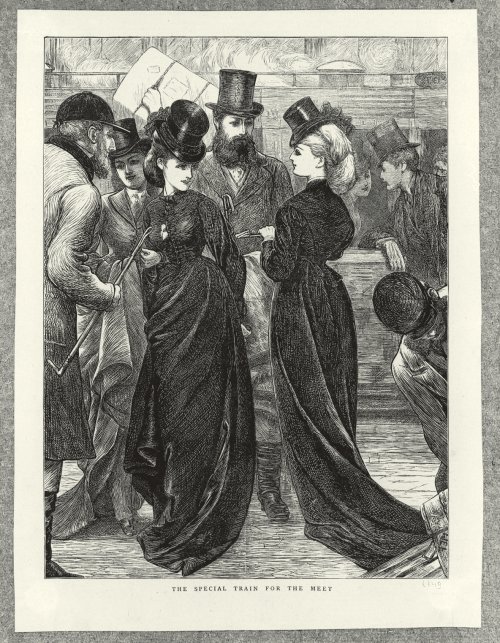

However, even for the Victorians, black could be chic and sexy, and on women as well as men, as seen above.

…two handsome young women stand with assurance in the centre of the carriage, both in long trailing black riding-habits and with neat, too-small black top-hats fastened tilted over their brows (one holds up her riding-crop as a fence between her and an amiable gentleman)…. The smart black of the riding-habit, together with its pretty mock-masculinity, doubtless enhanced the excitement of escaping from the crinoline by getting on a horse.

Pg. 203

We can easily see the prototype of the dominatrix, taking on male sartorial elements in a sexy way. In Venus in Furs, Wanda generally wears black and/or white (while her three African handmaidens wear red).

One might even draw a confirmation of the point from Sacher-Masoch’s novel Venus in Furs: for the Wanda the hero loves is his Venus, white either in her ‘white muslin dress’ or out of it, and he derives the same erotic charge from seeing sable fur wound either round her bare body, or round her white-dressed body. In Venus in Furs one sees the final inner work of the dark clothing in the psyche, as black-on-white ascetic harshness is naturalized (fur not cloth), wedded to death (the furred animal is dead), and eroticized in a desire for punishment, to be inflicted by a whitened woman both bare and clad in black.

Pg. 220

The punishment aspect, or perhaps a generalized sense of power and judgement, of black appears in Franz Kafka’s The Trial, in which most of the men wear black, but “ranks and roles in the novel may reverse.” (pg. 229)

But in the cupboard-like room itself stood three men, crouching under the low ceiling. A candle fixed on a shelf gave them light. “What are you doing here?” asked K. quietly, but crossly and without thinking. One of the men was clearly in charge, and attracted attention by being dressed in a kind of dark leather costume which left his neck and chest and his arms exposed. He did not answer. But the other two called out, “Mr. K.! We’re to be beaten because you made a complaint about us to the examining judge.” And now, K. finally realised that it was actually the two policemen, Franz and Willem, and that the third man held a cane in his hand with which to beat them.

Black is an extremely complex and multi-layered sign, and when you add history, there’s a whole new dimension of complexity and meaning. “Meanings change but older meanings cling, with something like the tenacity of a stain on cloth.” (Pg.13)

At issue here are the more intimate, and more potent, aspects of dress. For while dress my shield a private vulnerability, there are also ways in which, in choosing to wear certain clothes, on may be not so much adopting a cover, as conjuring a new persona for oneself…. In dressing we enter an inheritance, which many include a new self, which we feel to be a ‘true’ self, revealed or rather realized by the donning of these good clothes.

Pg. 14

Harvey links the early 19th century dandies, who largely pioneered all-black men’s clothing, to ascetic, even masochistic, practices. (Pg.34)

In discussing Jane Eyre’s masochistic relationship with Mr. Rochester, Harvey brings up mating.

In human sexual selection, black is not only a smart glossy coat: it is also daring and can be dangerous, and a sign of dangerous sex. It easily alludes to death and pain, and can heighten the excitement of damaging and binding. These last ‘black’ values are at least in part culturally derived: witness the fact that black has not always been as important for pornography as it is in our time. That is to say, part of the sexual excitement of black derives from the values black has had in society; and that these values have been dark indeed is clear from the testimony of Baudelaire and Dickens.

Pg. 38

This book almost exclusively discusses men in black, but it does include the tidbit that the Furies of the Ancient world were said to wear black in The Choephori and The Eumenides. (Pg. 43) The prototype of the dominatrix? (Note that Matilda in Matthew Lewis’ The Monk also wore sable, or black.) In the Middle Ages, black was the attire of the unrequited lover, of melancholy or masochism. (Pg.51)

Another famous group of men in black are the Jesuits. Ignatius, the founder, actually dismissed priestly uniforms, as well as “dismissing as spiritual luxury the customary observances of priestly asceticism, such as ‘fast, scourging, going bare-footed.'” (Pg. 84) They adopted a black uniform, which influenced school traditions, and which Protestants pointed at to depict the Jesuits as a sinister Papist army.

Shakespeare’s two best-known men in black (clothing for Hamlet, skin for Othello) are ambivalent, tortured figures, manipulated by others, and have a way of being fatal to the people around them, particularly the women closest to them.

Black was also associated with the Carnival of Venice in the 18th century, with black cloaks, hats and dominos (masks), worn by men and women, indulgence before the denial of Lent. “It was a prescribed period of de-prescription, with an anti-uniform that concealed difference, which in masking the person freed the person, and which under the don’t-see-me colour of black allowed what was not to be seen to be at once visible and disguised.” Pg. 124

For our discussion, Harvey suggests two common themes of black clothing.

The first is that black is the preferred wear of ascendant elites, before they achieve their goals and slide into decadence. Not only was the British Empire at its peak run by men in black (except in the tropics, where colonial officers wore gleaming white), so was the Spanish empire, emulated a few generations later by the French during the rise of their own empire. It suggests a rejection of the existing social classes, and creation of a new class of power and destiny, one that is serious and means business. This fits BDSM culture’s sense of itself as avant-garde, providing the wearer a sense of initiation into a new society that is self-disciplined, exciting and daring. It is the wear of a person undergoing regeneration, in a liminal state. “…when you have put on the Black Shirt, you will become a Knight of Fascism, of a political and spiritual Order. You will be born anew.” (British Fascist newspaper The Blackshirt, 1934, quoted on pg. 240)

… as the ruthlessness and cruelty of Fascist fact, in becoming a memory as those years recede, becomes a thing of fantasy: which becomes a fantasy of sadism, and so a fantasy-sadism, a sexual buzz. And not, after all, only for youth either, for there is a pornography for all ages that procures its fix not from putting on SS gear but rather from putting SS gear on women, from having a girl arrange a compromise between being naked and being dressed like an Obergruppenfuhrer – as she fingers the implements of correction.

Pg. 243

The second is that black suggests violence, which may be outwardly directed, as when worn by the soldier or the outlaw (i.e. the sadist), or inwardly, as when worn by the ascetic or the mourner (i.e. the masochist), or delivered from above (i.e. the judge or priest). The near-universal black of Dickens’ England indicates, to Harvey, a society built through and permeated with violence justified by Calvinist-capitalist ideology.

The black of mourning may originate in a violence of grieving, and a violence against the self is part of the whole story of asceticism; but it is violence not only against the self, but against others, including the innocent….

Pg. 113

It has become a folk intuition, that in putting on black leather you are putting on power: it may the power that defies the law, it may be the power that enforces it.

[…]

Given the complicated relations of Eros and Thanatos in human sexuality in any case, it is not hard to understand how black, with its acquired associations with discipline, sex and power, can be an efficient trigger and excitant, the more so when the practitioner, rapt in sexual mechanism, binds with black leather, or its deader-still surrogates black plastic or black rubber, the tender human body.

Pg. 245

This made me curious about women in black (starting with nuns, perhaps?)