Last month, DoubleX.com ran a feature called “Why Do Girls Love Unicorns?”. This also introduced me to the useful term of “cullenization.”

Women have been linked to unicorns since at least the Middle Ages, but in the early days, our horny friends were decidedly uncuddly, and they weren’t even particularly sparkly. Spend a few weeks poking around in the history books, and you begin to see how unicorns have suffered a centuries-long Cullenization: a slow transformation from a creature both dangerous and seductive to something mincing and insipid, best suited to serve as a decorative motif in little girls’ bedrooms or the apartments of slightly cracked adults.

The earliest mention of a four-footed, one-horned animal in Western literature comes courtesy of Ctesias of Cnidus, a Greek physician who plied his trade for the king of Persia. In his fourth-century B.C. work Indica, Ctesias describes an Indian wild ass that had a crimson, black, and white horn some foot and a half in length. This creature is “exceedingly swift and powerful,” he writes, and tears into its enemies with “horn, teeth, and heels”; it “cannot be caught alive,” and if it’s approached in combat, it will “kill many horses and men.” (Ctesias did note that the ass had “the most beautiful ankle-bone” he had ever seen.)

…

The most popular myth about unicorns takes this image of a tough, wild creature and adds two crucial elements: women and sex. According to this enduring story—the exact origins of which are a bit fuzzy—the unicorn is an uncontrollable beast that can only be captured if a pretty young virgin is dangled in front of him. The girl’s innocence proves so intoxicating that the animal goes all weak-kneed and submissive, at which point the hunters pounce and bag their prey. This is the scenario depicted in the famous Unicorn Tapestries that hang in New York’s Cloisters museum and in countless other works of art.

This ritual encounter of the rampant masculine and the feminine was once sublime and frightening, a kind of ritual combat. Over the centuries, this primal scene became so familiar that the sublimity was leeched out of it.

As CS Lewis pointed out in the introduction to The Screwtape Letters, angels used to be effing scary. In the Old Testament, when they appear it’s usually to ravage a city or turn people into pillars of salt or something. That’s why in the New Testament, when the angels appear to the shepherds to tell of the coming of Christ, they have to say, “Fear not, for I bring you tidings of great joy.” Talking to an angel was like talking to a armed nuclear weapon. In Lewis’ time, however, angels were depicted as nurturing feminine figures who say, “There, there.” Aslan, Lewis’ Christ figure in the Narnia books, is often described as “not a tame lion.” Lewis wanted a Christ figure that was sublime, not just beautiful.

The latest film in the Twilight franchise is New Moon, which is organized around a love-triangle between Bella, a Native American werewolf and a sparkling vampire. If Stoker’s Dracula and Sheridan le Fanu’s Carmilla were the new generation of seductive vampires, they were also strongly associated with the racial/ethnic other of Eastern Europe. In other words, they weren’t white. Stephanie Meyer’s vampires are strongly associated with whiteness, with extensive references to Edward’s white skin, so lustrous it actually sparkles in direct sunlight, and to upper class-aristocracy.

Somewhere along the line, a monster stops being scary. This must be a sad moment, which a creature stops lurking in the dark woods and starts appearing on lunchboxes.

Some monsters handle this well. Frankenstein’s Monster and King Kong are both destructive yet tragic creatures. Others dont’t. I’ve often wondered why Godzilla, a walking embodiment of nuclear annihilation, became a crude anti-hero to Japan in later films.

This can be positive, though. Marlene Dietrich’s character, Lola Lola, in The Blue Angel (1930, based on the 1905 novel Professor Unrat, is meant to be a sign of the seductive, decadent feminine which threatened to degrade the male professor’s intellect and drag him down into decadence. She’s the bad guy, the monster. Now, 79 years later, Dietrich as Lola is an icon to women and queers, the very people who would have been seen as monsters to the people of 1930. Monsters become heroes become monsters.

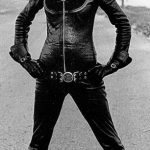

The dominatrix, a distant descendant of the femmes fatales of late 19th century literature and earlier, is just such an unstable figure.

At this point in history, on the brink of 2010 (a date which seems slightly unreal, belonging in fiction not fact), is BDSM loosing its sublimity? Has the nebulous category of “rough sex” supplanted BDSM as the edge of human sexuality?