It’s been said that Hallowe’en is Christmas for queer people, but if there’s a holiday for kinksters, it is Good Friday. This is the day when a man was tortured to death for trying to get people to be nice to each other.

While I don’t have this quite figured out yet, I get the impression that the primacy of the Passion, the story of Jesus Christ’s betrayal, murder and resurrection, was a late medieval invention, and earlier depictions of Christ in graphic art and storytelling focused on his life as teacher and miracle-worker. The violence of the Passion came later. One person I know suggested that the cult of the Passion coincided with the Crusades, violent art reflecting a violent society, or even as intentional anti-Semitic propaganda.

The Passion, as a story, became familiar throughout Christian society, depicted in a myriad different ways. While there is a core of essential characters, objects, props, and moments, there are also endless variations. Even the four canonical gospels disagree on many points, minor and major, so there are textual gaps for other artists and writers to exploit.

In some images, Christ is depicted as superhuman, tranquil or even smiling on the cross, his body invulnerable.

In others, Christ’s humanity is emphasized by showing his suffering, with his face anguished and his body emaciated, grey, wounded, bound or nailed to the cross, flagellated. He is the “Man of Sorrows”. Not only was the reader/viewer impressed by the magnitude of Christ’s suffering, he or she would sometimes meditate on or even emulate the example, through self-flagellation or the like.

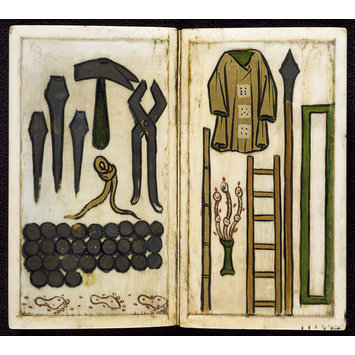

Some of these images are highly stylized or even iconic, such as specific “props” presented without context, assuming the viewer will be able to read them as part of the familiar narrative of the Passion. Examples include the crown of thorns, the thirty pieces of silver, or the wound in Jesus’ side (represented as a red lozenge-shape or an oval with drops of blood) decontextualized from the body. These were known as the Arma Christi, with a focus on the particular implements or the results of their use.

This, of course, informs Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, in which the centrepiece is Christ’s suffering body. The injuries inflicted on him are inflicted with a greater… I don’t want to say “realism”, but intensity, than ever before. Gibson’s film is obviously a devotional work, and the experience of watching it is effectively a devotional act. As I discussed in other posts, Passion-based works vary greatly in how they depict Christ’s suffering: at one extreme, they are highly abstracted, while at others are highly concrete (though not necessarily realistic, again).

Some of these are “strong misreadings” (as in Harold Bloom’s theory) or “perverse” readings of the Passion, reading against the official interpretations of this story. To modern Christians, this fixation on Christ’s suffering, his corporeality, his depiction as nothing but suffering flesh, must seem odd, even perverse. I don’t think this is a necessarily more primitive or underdeveloped form of religious faith than any others. It is a more personal, visceral form of devotion, perhaps one that solves the paradox of the Christian attitude to the body: the body is a source of suffering, but through that suffering one connects to the divine. Today, post-anaesthesia, we view suffering as something to avoided when possible and to be hidden when necessary. When we see the “Kristianos” crucifying themselves for real in the Philippines on Good Friday, we are horrified, not awestruck by their piety and devotion.

In the transition from the medieval world to the modern world in the West, one of the myriad changes was the shift (over a period of centuries) in how people viewed ecstatic physical experience. An anonymous critic called Bernini’s life-size sculpture of the transverberation of St. Theresa of Avila as “not only prostrate but prostituted.” St. Bernardino of Siena complained of a person literally masturbating while contemplating the humanity of Christ on the Cross. The eroticism of Passion devotion had irrevocably split from the spiritual. You can’t unbite the apple. And so, we have five centuries and counting of religious sexual parody. All those icons and paintings and sculptures are still there, stuck in our collective unconscious, turning up where we least expect it. Even among the irreligious or even the atheists, these memes or tropes are still there. Remember, Anna Freud only glimpsed the book on medieval knights she later wove into her spanking fantasies.

This could explain how BDSM seems to a particularly Western, Judeo-Christian phenomenon, only relatively recently exported to other cultures: it is a perverse reading, or strong misreading, of Christianity itself.

Came across this arlcite from @edencafe on Twitter. I think your comparison here is interesting. But there’s a huge, crucial difference. In BDSM, my understanding is that the majority of people in that community are there by choice. If someone is in a master/slave relationship, it’s because that is what fulfills them sexually. At least, that’s the ideal that this community espouses. And if at some point, a person in such a relationship decides it’s not for them any more, they ought to be able to leave unless it has turned into an actually abusive relationship, which is a different matter altogether.However, in the conservative Christian culture, there is not that choice. A man is expected to be the leader whether or not that is what he prefers. A woman is expected to be submissive again, regardless of her personal preference. And that power dynamic is not just limited to the bedroom. It extends in many Christian churches to all aspects of life and to everyone in the congregation young, old, married, not married. To go against that setup is to risk being alienated and harshly judged. It has nothing to do with what is sexually fulfilling for a particular couple. It is considered the way things ought to be for everyone and for all time. It’s not like that in all Christian communities, though. And there are some truly happy marriages within that patriarchal framework. But there are also many deeply discontented people and people for whom this system is damaging and wounding. One more thing Christian theology doesn’t teach a master/slave relationship. God is imaged as a loving parent, as a lover, as a friend. Serving is presented as a mutual activity, to be done first by the strongest on behalf of the weakest.